This Week’s Bit of String: Ewoks and hippies

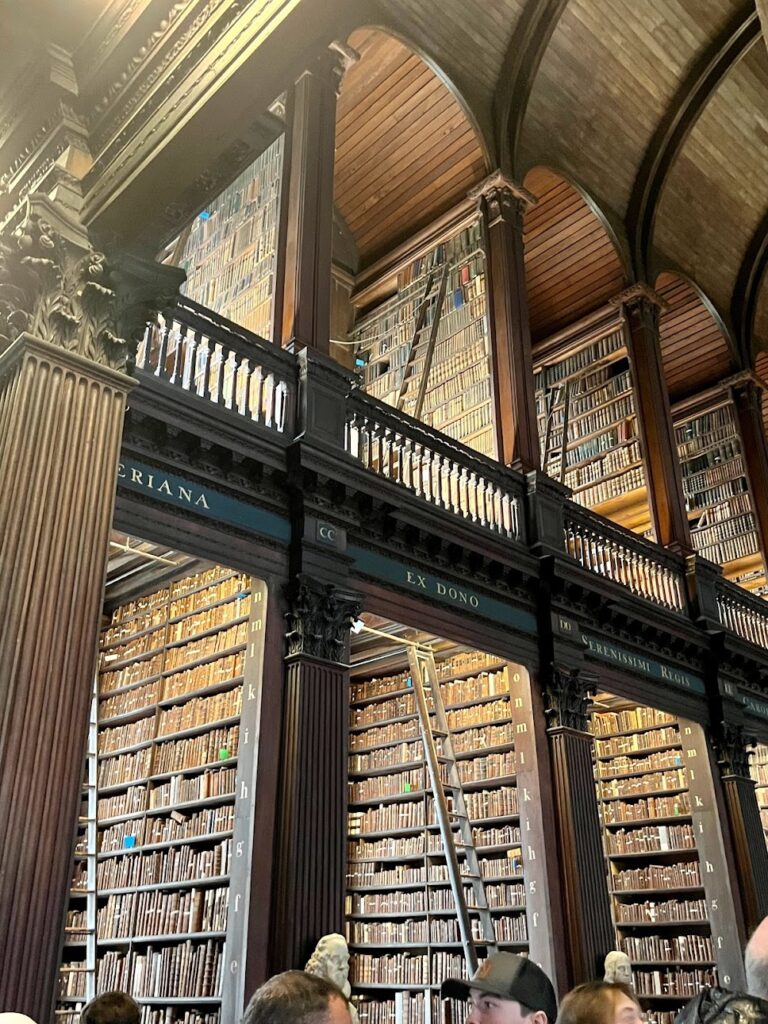

For the first Literature class I took at university, my professor resembled an ewok. He was gentle and diminutive, with a pointed snowy beard in place of a neck, and he would pace the room in a curved trajectory as he delivered lectures on Early English Literature or Science Fiction. Soft-spoken but passionate about his subject, he would pause when he’d gone over something significant, and tilt his head, his black eyes twinkling, and say “Hmm?” as he gave the sleepy morning classroom a moment to consider.

Another Literature professor paired silk scarves with sweatsuits, and when she felt she’d offered a particularly profound insight, she’d raise her hands palms up and intone: “Mmmmm!” as if she were a medium for divine inspiration. And I took a British Victorian Poetry class from a woman in her twenties who insisted, with poor reception, that we write “womin” instead of “woman” and “womyn” instead of “women.” She was brittly nervous and read us Sonnets from the Portuguese with her arms clasped across her chest.

At university I relished the quirks of our instructors. There wasn’t a uniform vibe about them; they were quite individually eccentric. I’d had an idea that all writerly folk would be like the storyteller who used to visit my elementary school. She was a hippie type, with loose printed clothes and glasses and long fingers. She liked to sit us in a circle, lights dimmed, and always began by telling us how when people listen to a story, their heartbeats synchronise into a united rhythm.

It’s reassuring to think we can be spectacularly unique yet somehow fit in with a class of creative people. I say reassuring because I sometimes get dispirited by the headshots and bios in hit novels. Young faces with perfect hair. Masters degrees from top-tier universities. A lot of us are slogging through the working world and life overtakes us.

Props and Costumes

How then do we identify ourselves and others as writers, when there’s room for so many types? I doubt my students look at me and think I’m a writer at heart, apart from when I subject them to some dorky etymological or literary tidbit. I don’t have a caffeine or fancy pen addiction, so action figure Mrs. Parker does not come with cute travel mug and posh stationery.

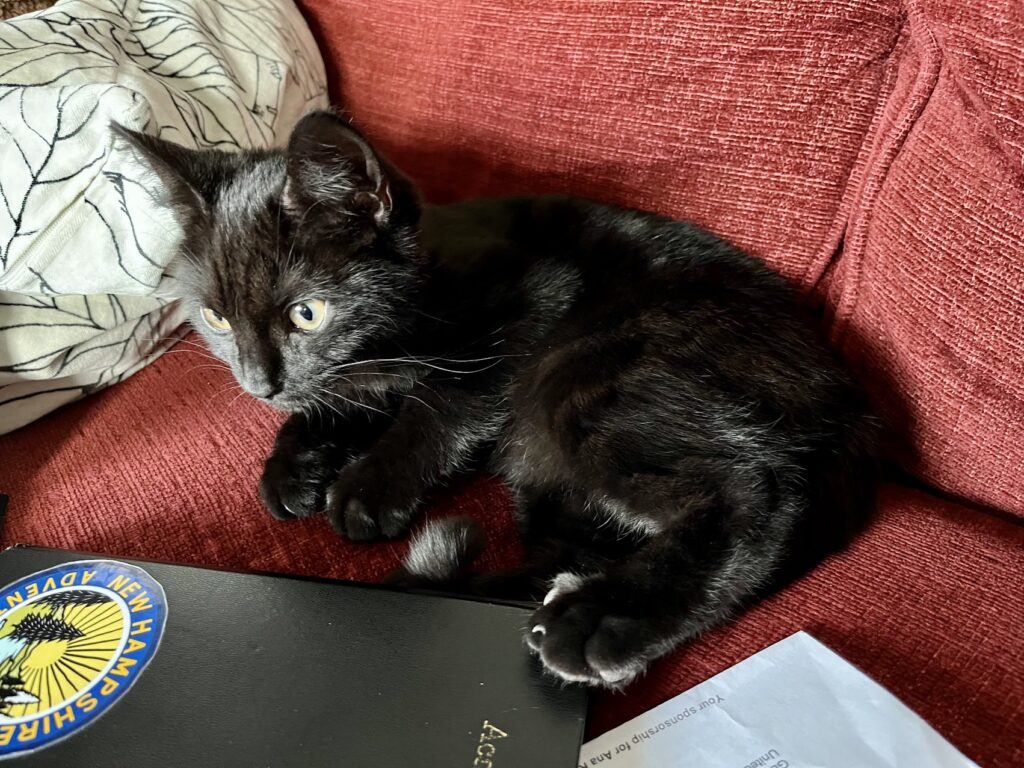

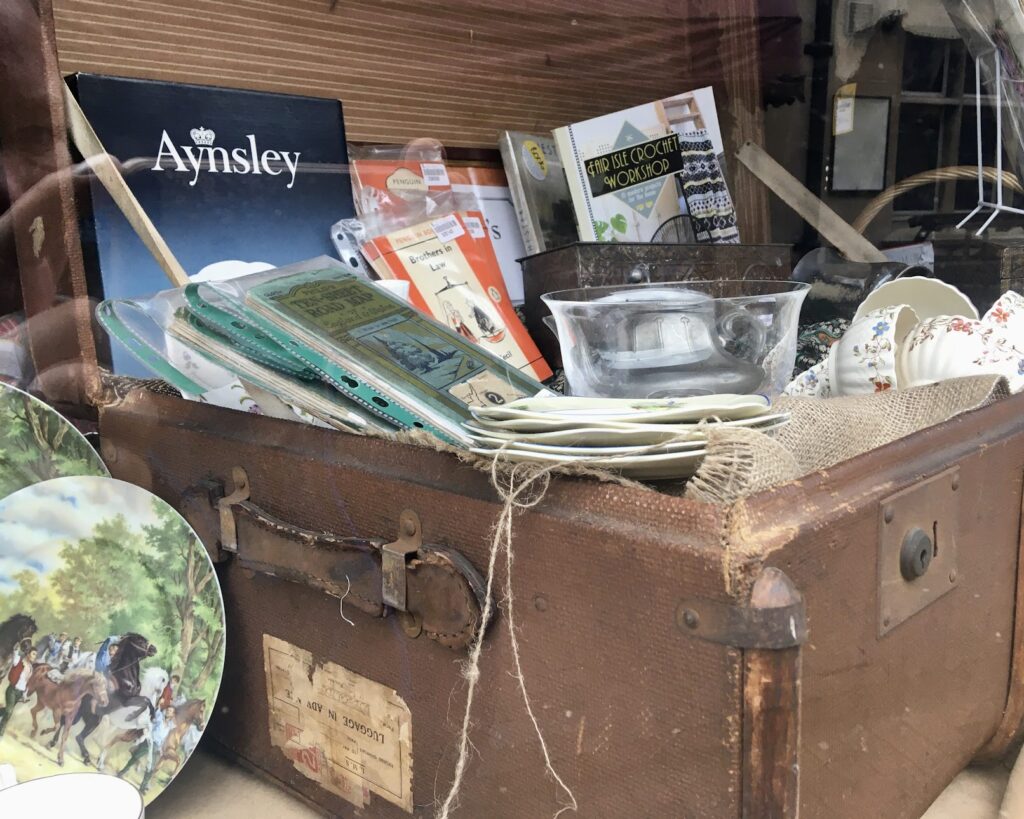

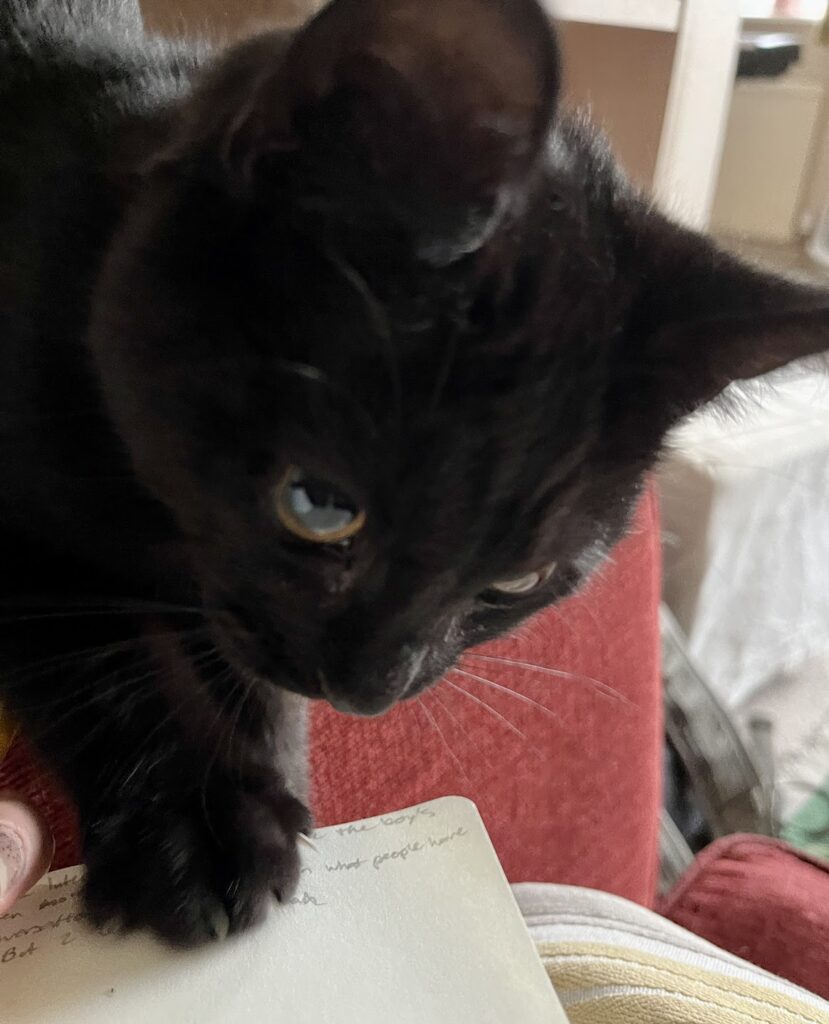

The writing life is partly about accessories. We hoard notebooks and probably have strong opinions about pens versus pencils (the latter for me!) Mugs and hot drinks, window views and scented candles or essential oils, Twitter handles, background music and feline companions join the Generic Writing Starter Pack.

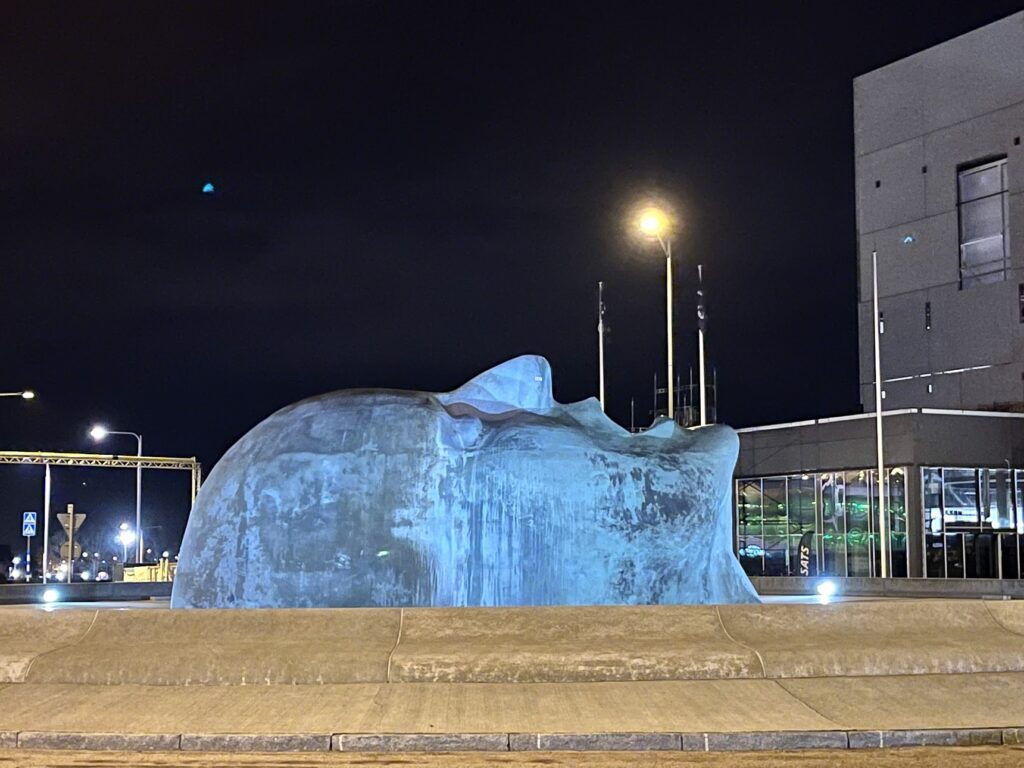

We may have to dress warm, lest the cold in our Bohemian writing garret doesn’t sicken us. Or dress fashionably for writing in a cafe. If I’m writing out of the house, I’ll be hiking there so my outfit will include muddy trainers, a hoodie, and earbuds. If I’m in the house, it’s probably really early morning and I’m in my pyjamas and again, a hoodie. It’s not glamourous, but there is a thrill in having something so important to say, it can’t wait till the world wakes up.

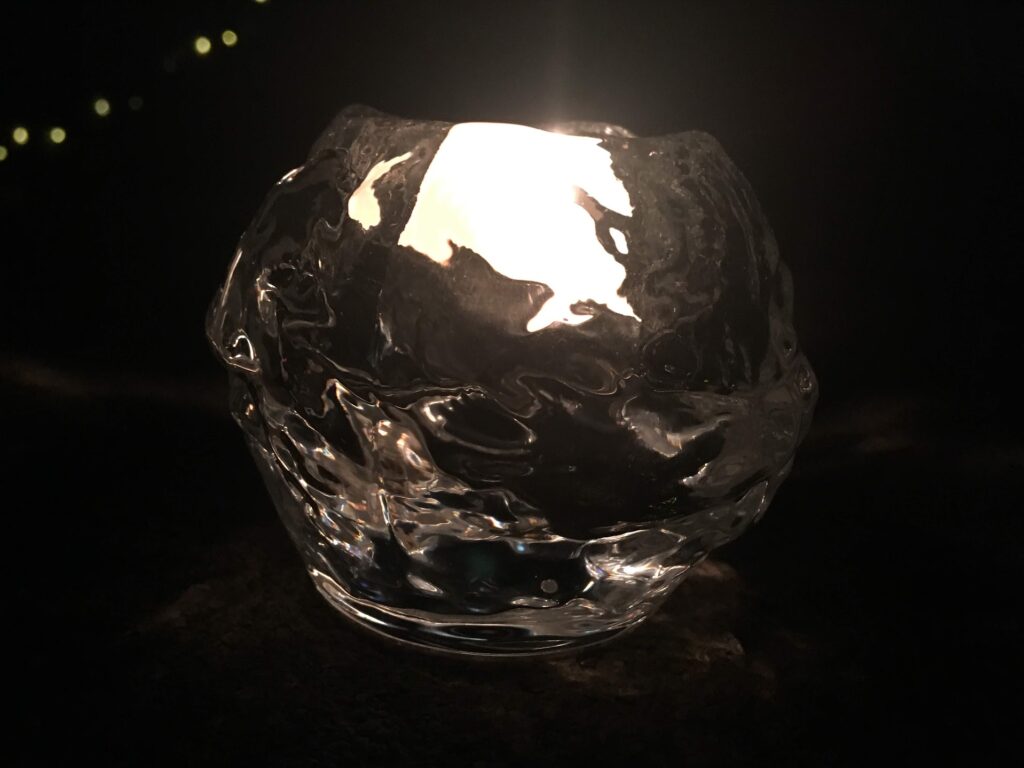

Looking honestly at it though, I work best when I’m properly sat up at the dining room table and dressed to feel awake. I’m best if I’ve eliminated the possibility of going back to bed for a catnap at 9, when I’ve been up at 5. A hot drink is good, and a candle with a stiff refreshing scent–I love something woodsy.

More Than a Feeling

These things sound trivial when stories need telling; these trappings of clothing and seating and utensils. But it’s worth a lot to feel like a writer. Our solitude can be pervasive, and successes sporadic. We are storytellers and we need to first convince ourselves that our voices are significant. Weaving some sort of authorish aura around ourselves is our first essential persuasive task.

I imagine being the classy sort of writer who drinks earl grey tea and can write for hours in a cafe wearing stylish blouses and boots without the need to curl up somewhere quiet with a brownie. Wouldn’t I be cool? Then again, being a hoodie-type writer suits me because it connects me to so much outside my writing: my busy Teaching Assistant work, my family, my love of walking and exploring. Those inspire my writing and I’m proud to be tethered to that reality.

Of course, we don’t want to be overly dependent on our image, even if we think we’re cultivating it for our own sakes. A great story can be told as well on a beat-up laptop as in a leather-bound notebook. Our writerly props may motivate and inspire us, but without them we can still bring stories into being.

Feeling present in ourselves and in our writing is perhaps the best accessory we can acquire as writers, whether we wear blouses or sweatsuits or snowy beards. I say being present instead of being confident because who among us will always be confident? We can use insecurity and anxiety in our creative process to convey those aspects of the world, we just need to face them honestly.

Do you have writerly accessories that feel essential? What’s their story?