This Week’s Bit of String: A warren of ruins

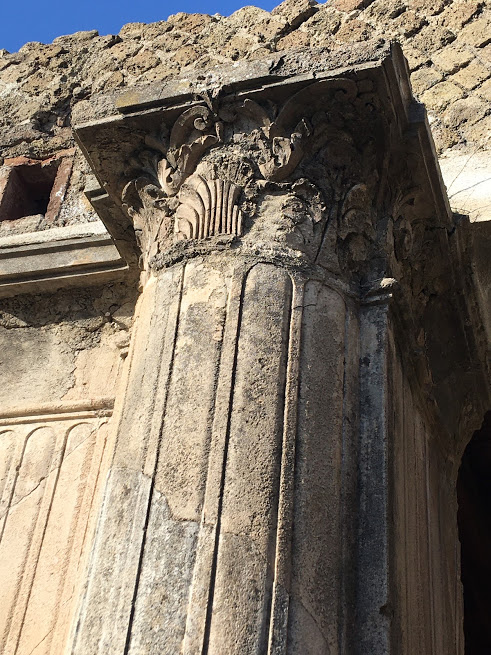

The street of battered pizzerias and pale, boxy apartment buildings descended toward the Golf of Naples. Through a park gate flanked by palm trees, modern blocks fell away and we saw labyrinthine city remains, built with early cement bricks. Herculaneum.

Many of the houses had beautiful mosaics and painted frescoes. While Mount Vesuvius crouched in the background, we marvelled at the technique and skill still visible. But I struggled to imagine the real people who lived there. Their skeletons looked so small, huddled beside what used to be the seafront before the volcano dumped its ash, killing over 300 in seconds.

We can see they liked some colour on their walls, liked soaking in the baths. How did they feel about growing up, coupling up, having kids, watching them move on? Did the mums wake up early to go for seaside walks before anyone needed them? When the houses stood, did they look as alike each other as the modern apartments do?

When we consider history, we can only imagine it in reference to the present: these things are the same, these are different. It’s the same way with people, I think. We compare and contrast people to ourselves. We have sympathy: this person is like me; and hopefully we develop empathy: Ah, but this person is different, in other ways—I wonder what that’s like for them?

This week I helped host a Twitter chat for our Women Writers’ Network. The subject was personal writing—how much of ourselves do we show? It generated interesting discussion on memoir and autobiography, on crossing the boundary from reality to written word. Even fiction writers like myself often get asked, ‘Is it about anyone I know?’ Always with a hint of a nervous laugh.

It occasionally is, but you probably won’t recognise them. Here’s why.

Repurposing the Remains

Wandering through ruins, the missing bricks strike my curiosity as much as the standing ones. Centuries ago, did people cart some off to build roofs over their own heads? I researched the seven wonders of the ancient world recently for a short story. The pyramids, of course, were looted. Bits of the Colossus of Rhodes were sold as scrap metal, and blocks from the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus fortified a castle.

We see things for their use to us, not always their intended purpose. Any anecdote or personality trait we snatch, it changes to fit our story. We can’t replicate reality because the context always gets tweaked.

When I was 11, I planned my first fiction series. The protagonists were based on favourite book characters, or shared characteristics with my own friends. I felt bad about it. Why wasn’t I clever enough to make up my own characters?

You wouldn’t have detected the source material, though. If anyone had read my crammed pencil scrawls, they wouldn’t have recognised my crush as the hero, because to make him heroic I had to put him in situations he’d never dream of. Plus, in real life he barely spoke five words to me, so I was basically making him up anyway.

Assuming a personality is made up of elements both natural and nurtured, none of these elements will weather the writing process intact. (More on this process here.) Any nurtured aspects will be altered by the scenarios they’re penned into, and any natural aspects are only guesswork on the author’s part. We can never fully know another person. I wouldn’t even bet I could duplicate myself on paper.

The Sacred Template

Another lesson I take from my adolescent experiments with character-snatching is that I needed a template. I didn’t know nearly enough about people to create well-rounded, imaginary new ones. Do any of us ever fully get there?

It’s like when you start in a job, for a while you aren’t sure if your correspondence will be good enough, so you use the provided templates. Then you know it by heart and you can write your own, maybe omitting inconvenient phrases such as “Please let us know if you have further queries.”

Sometimes we can’t help it. We encounter someone or hear about something and just have to create our own version. That’s allowed. The writing can still be complex, made up of clever disguises and massive leaps of projection. For example, I recently finished Madeline Miller’s wonderful book Circe. We read modern retellings of myths even though we know what will happen in the end, because we want to see how contemporary authors will make the characters accessible.

Our renderings of reality are also subject to the constraints of our craft and its current fashions. They say people once feared photography would steal a piece of their soul. In a way, pictures and stories do that—because they can only preserve so much. We may try to portray diverse characters, but we can only snapshot them and in today’s literary world we might get caught up in the great distillation race: How few words can I use to convey this life, how succinctly can I sharpen a person’s image?

I’ve said since working toward my degree almost 20 years ago that I write to remember, to recreate people and places I can’t get to. But I found early on that while I always love my characters, a figment of memory is not an equal source to a real person. The idea becomes a new person as I try to create.

It could be discouraging, the realisation that we can’t fully understand people beyond the corruption of our own perceptions and experiences. It probably means pure altruism isn’t possible. But it also means we all remain originals. The most brilliant writer ever to pick up a pen could not recreate you or me. So stay weird, folks, no one can steal that from you.