Predictably, it was all British hikes last year. No European cities or the mountain lakes of home. Still, I’m lucky to live with countryside a mile away, to step out my door and choose a walking circuit of 3.5, 4.5, or 6 miles.

Weeks went by when we weren’t allowed even to drive a few minutes and explore Somewhere Else. Temporary easing of restrictions assigned extra value to sojourns that might otherwise not have been so memorable. And when we couldn’t travel, we could look to rainbows or holiday decorations. I think the people who put out massive displays of festive lights and inflatables by the third week of November, brightening the long nights, deserve to have a street named after them.

Dursley: Our Own Town

We’ve been familiar with the local hills for some time, but lockdown meant perusing churchyards, looking up name origins, finding the rare street less homogenous and more individualised than others.

Living in houses squished right up next to each other is hard. The constant reminders of other people practically on top of you, it’s exhausting. And when we fled for our daily walk, there were always a number of people doing the same. My son and I discovered more paths to the river (now more of a stream) and I may have gone mad without access to water in nature. Every day I incorporate the river in my walk, take my headphones off when I reach it, tell it hello, listen to its hurried reply, and imagine I could be on a riverbank anywhere in the world, letting it drown out the traffic and forgetting there are houses lined up on either bank.

Making a splash

The local peak with its spring robe

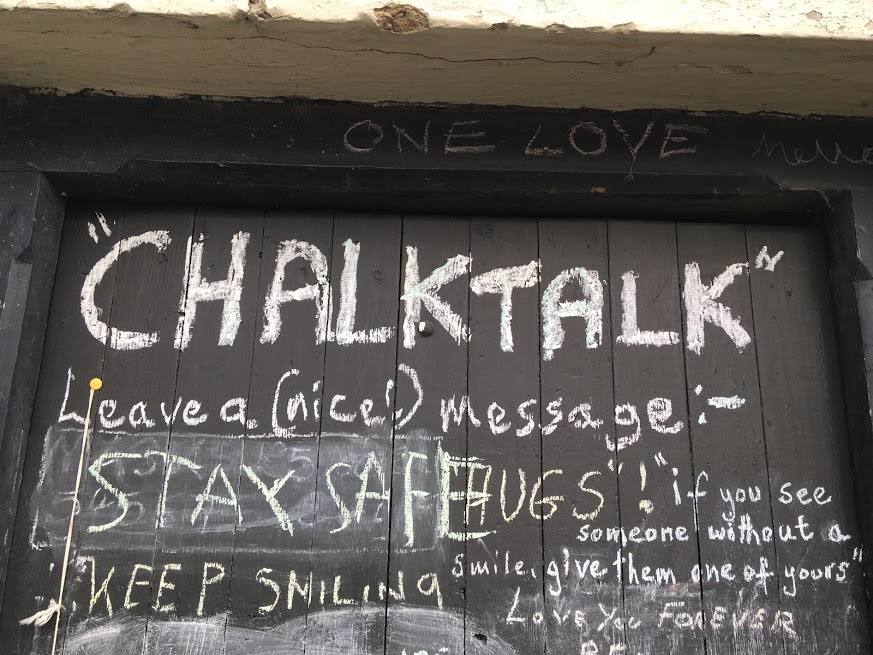

Community.

Rainbow collage made from townspeople’s photos

A hoarfrosty morning

Town Christmas decorations. Some more condomy than others.

Stroud Area: Selsley and Thrupp, A Few Miles Afield

My office is in Stroud so I used to go to this vegan hippie haven every day, walking the canal towpaths, listening to street musicians, frequenting little shops. For 3/4 of this year we could barely go at all. But our first journey out of town (by 7 or 8 miles) in the summer was to Selsley Common to see the dinosaurs, and my husband and I took a couple of canal walks later.

Dinosaurs made of rock shards

Local artists decorated Thrupp’s bus stops

One of my favourite shops: A Large Fancy Room Filled With Crap

Woodchester: Local Lakes

Where I grew up every little rural town has its own lake plus various other ponds. That’s how you cool off in the summer. Over here, despite this Island being known for rainfall, there aren’t many accessible bodies of water. We had a couple of hikes (as did many others it would seem) at Woodchester, a National Trust estate with pretty combinations of wooded hills and manmade lakes, guarded by an unfinished gothic-style mansion which is pretty much the sort of place I intend to set my next novel.

You know you want to read a novel set here.

Summer snow: wild garlic

The boathouse

Liverpool: Street Art and Maritime History

We managed to get a serious road trip in before this vibrant, friendly city was put into higher tier restrictions. With masks and constantly sanitised hands we explored museums to inspire whole fleets of stories: a branch of the Tate filled with modern art, the International Museum of Slavery, and the Maritime Museum. The grand if faded buildings still convey the city’s impressive history as emigration gateway and meeting place of cultures.

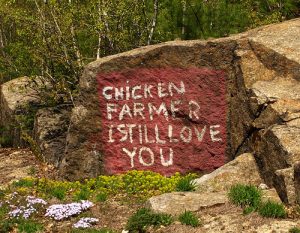

Of course there’s some street art on this list

Chinatown arch

Royal Albert Docks

Charmouth, Seatown, and the Dorset Jurassic Coast

Plan E to celebrate my 40th in December was a cottage near the sea and fossil-hunting under the coastal cliffs. Plans A and B would have involved seeing my family in the US—I haven’t had a birthday with them since I turned 23. In the end, we were incredibly fortunate just to have this break 2 hours away, as it fell in the 3 weeks between Lockdown the Second and The Raising of the Tiers. And although the weather was generally poor, it left plenty of fossils to be found.

Golden Cap, highest South Coast cliff

Fossil layer

My Boys at sunset

Combe Martin and North Devon’s Cliffs

As soon as the hospitality industry re-opened slightly in July, we went, for my first days off from work in months. Just to a cottage and lots of isolated hikes, mind you, no crowded beaches or anything like that. We love a bit of rock-scrambling and tide-pooling. The coastline in North Devon is pretty dramatic and made for good, even sunny, adventures.

Combe Martin beach

Pack of Cards hotel

Hangman’s Cliffs

Grasmere and Easedale Tarn: Proper Lakes

The main bit of our autumn road trip was spent a fair way North, in a Lake District shepherd’s hut with no electricity or running water. We hit Liverpool and the brief luxury of a half-empty hotel on our way back down. The Lake District is special for its own ancient landscape and language: fells and tarns and ghylls. Of course we hiked around Wast Water, England’s deepest lake at the foot of its sharpest peaks, and we visited lovely pubs and bakeries and came away with gingerbread and a glorious painting by Libby Edmondson. Our very favourite hike, though, was an unexpectedly bright afternoon walking along a beautiful purple-black river and ascending up to one of the glacial ponds, Easedale Tarn.

Just outside Grasmere

Sourmilk Ghyll

Easedale Tarn

Did you get to do much exploring in 2020? If not, did you find anything special and new in your own local area?