This Week’s Bit of String: Black, feathery carnage

On Tuesday, I came home from work raring to finish a story. I’d been unsure about it for the last month, aware I didn’t have the voice right and possibly insufficient trajectory, but just before my shower early in the morning, it suddenly came clear. I knew exactly what to do, I just needed to get through the busy schoolday before I did it.

Our cat Oberon, however, had other plans. As soon as I opened my front door, I saw that writing would be delayed. There were feathers all over the living room floor. Hundreds of little, downy, charcoal-covered feathers, sometimes in clumps. I froze in the entryway. Was a live bird trapped inside?

Obie quickly appeared, ecstatic that I’d finally arrived at his epic battle site. He’s ten months old, our lithe black beauty, and he’s a Mumma’s boy. He rubbed up against me, again and again, purring lustily. He ducked under the sofa and retrieved a blackbird corpse that was already starting to smell, thus answering my initial concern.

It took me a while to even face cleaning up, although I removed the bird and threw open the windows. By 9 p.m. I did finish the story, as I wanted to. By 9:30 Obie was curled up like a little dark foxlet on our bed, where he stayed snug between us for the night.

You wouldn’t have thought he was a vicious killer.

Dark Sides

Humans too are quite multifaceted, although hopefully most of us don’t prey on and then rip the life out of other creatures. We all assert control and manipulate circumstances, to varying extents.

Over the weekend, we had our annual outing to Cheltenham Literature Festival, and attended events pertaining to this complexity. David Mitchell (the comedian and actor, not the Cloud Atlas author) spoke about his book on historic royals, with his special brand of humorous pessimism. Progress isn’t necessarily linear; you never know when things might get a whole lot crappier, and there’s only so much power humans have to do anything about it. Not exactly cheery, and yet many laughs were had. It’s all in the telling.

Then we listened to Carmela Ciuraru interviewed about her book Lives of the Wives: Five Literary Marriages. This examines authors like Kingsley Amis and Roald Dahl, and their relationships with their wives (Elizabeth Jane Howard and Patricia Neal, respectively) who were talented writers/ performers in their own right. However, these towering male geniuses didn’t often treat their partners with the respect befitting, well, a partner. They were actually quite tyrannical.

Ciuraru doesn’t believe in ‘cancelling’ these figures, because she points out that we all have people in our lives who we love despite their flaws. Can’t we then love just someone’s art despite their flaws?

Furthermore, Ciuraru doesn’t think the work should be censored–we should be able to see the full evidence of the writers’ attitudes so we can make up our minds. For example, if the instances of Roald Dahl’s children’s books referring to characters as fat or other derisive terms are removed, people won’t see the evidence of his sometimes bullying nature.

Keeping Nuance Alive

It depends on your experiences of course, what you feel you can overlook in somebody, and it depends on what else they offer you. I remember being uncomfortable with some of Dahl’s books as a child, like George’s Marvellous Medicine and The Twits. The characters were so loathsome to each other. I loved James and the Giant Peach, but in that book no one intentionally harmed the villainous Aunt Spiker and Aunt Sponge–they got flattened by accident.

When I’m writing stories, sometimes people do awful things to each other. Because that happens in real life, doesn’t it? I’ve had my work called dark before, such as my story The Apocalypse Alphabet, about a mum and a boy and an encroaching invasion that feels like the end of the world. Sometimes I feel bad about coming up with these things. What does it say about me as a person, that tragedy and grief come out of my head? But it’s usually counter-balanced with moments of warmth, even humour, and strong relationships.

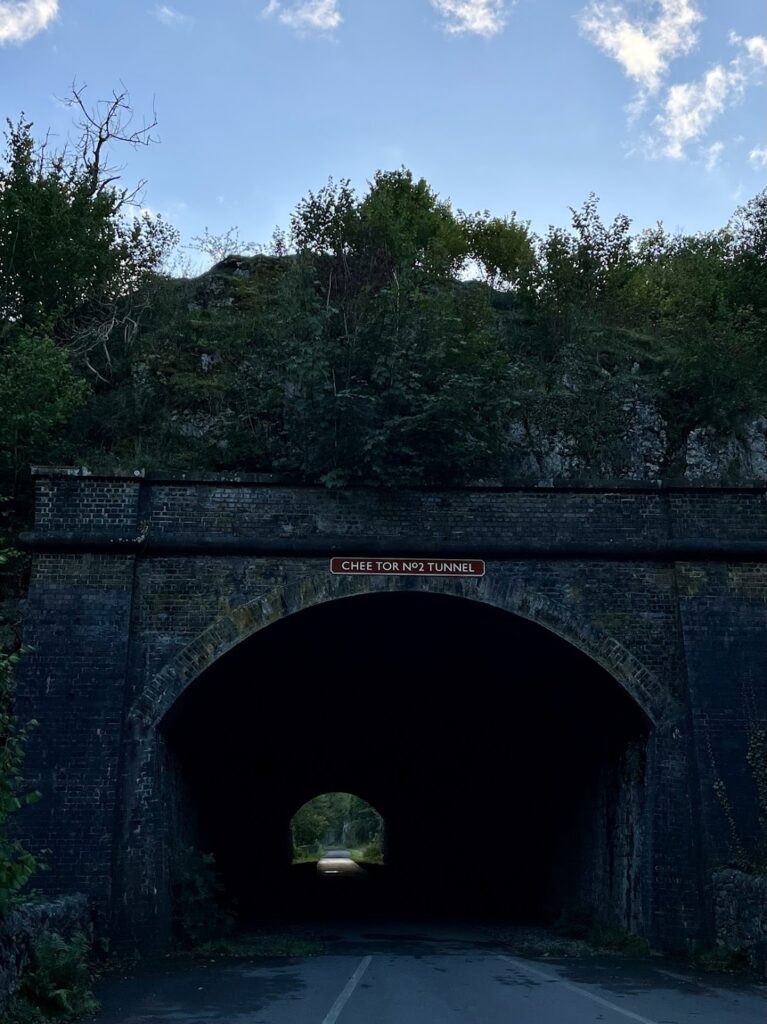

There’s very little that’s entirely dark, just as my kitten isn’t just claws and fangs. The story I finally finished drafting this week is a triptych with three scenes set in different graveyards. The main characters seek them out because they feel safest in gloomy, forgotten spaces. When you’ve faced how dark life can get, you may not feel comfortable in the light.

Funnily, I’ve always been afraid of the dark at night. Not the darkness outside, if I’m on one of my early morning hikes, but the darkness in houses, where you can so easily be cornered. When I was little, I tried treating darkness as a separate character. I told my mom I’d make friends with it, and we’d share jelly beans. Didn’t coax me out of my fear, but maybe writing dark stories now and then is a different way of befriending darkness.

How would you characterise your relationship with darkness? Does it work to counterbalance difficult subjects in our portrayals or should we let them be?