This Week’s Bit of String: Villains in the woods

Growing up, we were always acting out stories. We played them with stuffed animals, listened to them on cassettes, and ran through the woods pretending we were heroes with baddies after us.

We lived beside a rustic, lakeside resort in New Hampshire, and its cottages were scattered above us in the forest, empty until summer. We’d patter along the footpaths, assigning different storybook villains to each cabin. Maleficent, the White Witch, the Big Bad Wolf, Snow White’s evil queen, and the Wicked Witch of the West all holed up in those cottages.

Mom accepted that we never wanted to play the bad guys ourselves, so she’d put on a crone voice and play the witch part, chasing us along while we shrieked excitedly. She always had to be the villain in our games and by doing so, she gave our games and stories extra potency.

As thrilling as Mom made our childhood, I could never write her into my fiction. I sometimes take people or moments that I irresistibly return to, and put versions into stories. But my mother wouldn’t work as a character. She’s too good.

Having devoted every second of her life to four brilliant (I mean, you should see my siblings) but very weird, needy children, plus helping earn a living primarily working with special needs students in elementary schools, plus volunteering at church and generally being a magnet for waifs and strays… She is the Most Patient Person in the World™ and my mother couldn’t be believed if she turned up in a book.

In modern literature, she’d be covering up for something. Her good deeds would be belied by exerting painful standards on her children. But Mom is almost unfailingly patient, and while she sets high standards for herself, she loves knowing who we really are and accepts our differences. And she’s by no means boring, with her wealth of experiences and her exceptionally tolerant good humour.

The Good Ones

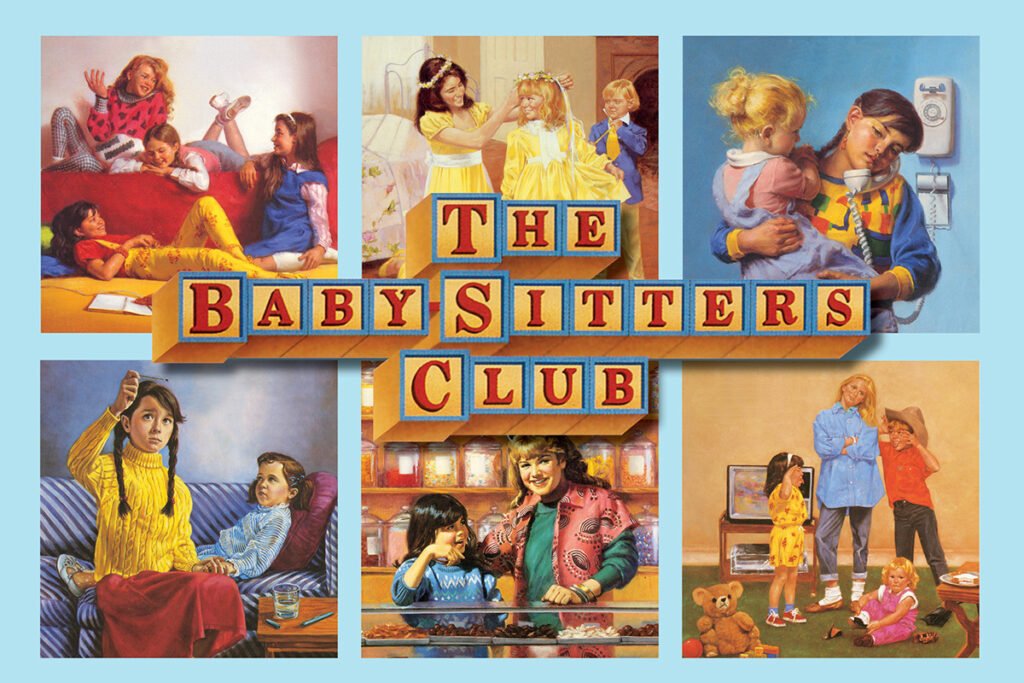

I aimed to do a round-up of good literature mums, and it was somewhat challenging. Just as many fairy tale villains are female, a fair few mothers in contemporary books are abusive (Elinor Oliphant is Completely Fine or Gillian Flynn’s Sharp Objects), manipulative and self-centred (Deborah Levy’s Hot Milk), or detrimentally submissive (The Glass Castle and Tara Westover’s Educated).

This might reflect people being more honest about how hard parenting is. Not everyone is cut out for the job. So many other mums in books are consumed with survival. This absolutely does not make them bad mothers, but it makes mothering secondary to the plot. It’s like when a sitcom couple has a baby and the baby is hardly ever in the show.

I’ve been writing about Eve, the “Mother of All the Living,” and motherhood looms large in my work-in-progress. But she isn’t a brilliant example because she had much baggage, and no one to emulate. I love reading and writing about mums that know their kids well, mums who, even for a brief scene, play whatever silly thing their kid likes and enjoy it, even while admitting that a parenting day can be long indeed. After all, my mom was like that, and as a mum myself, time spent with my Bear–doing anything, really–is my very favourite thing.

So I’m thinking of Elizabeth Zott in Lessons in Chemistry, who is honest with her daughter about how tough the world can be, but tries not to pass her sadness on. Supporting, defending moms like in Wonder or The Fault in Our Stars.

There are incredibly brave and devoted mothers like Mauma in Sue Monk Kidd’s The Invention of Wings, who is enslaved but gives Handful as much freedom as she can. The mother in Room by Emma Donaghue whose son is her whole life, quite literally, for 4 years.

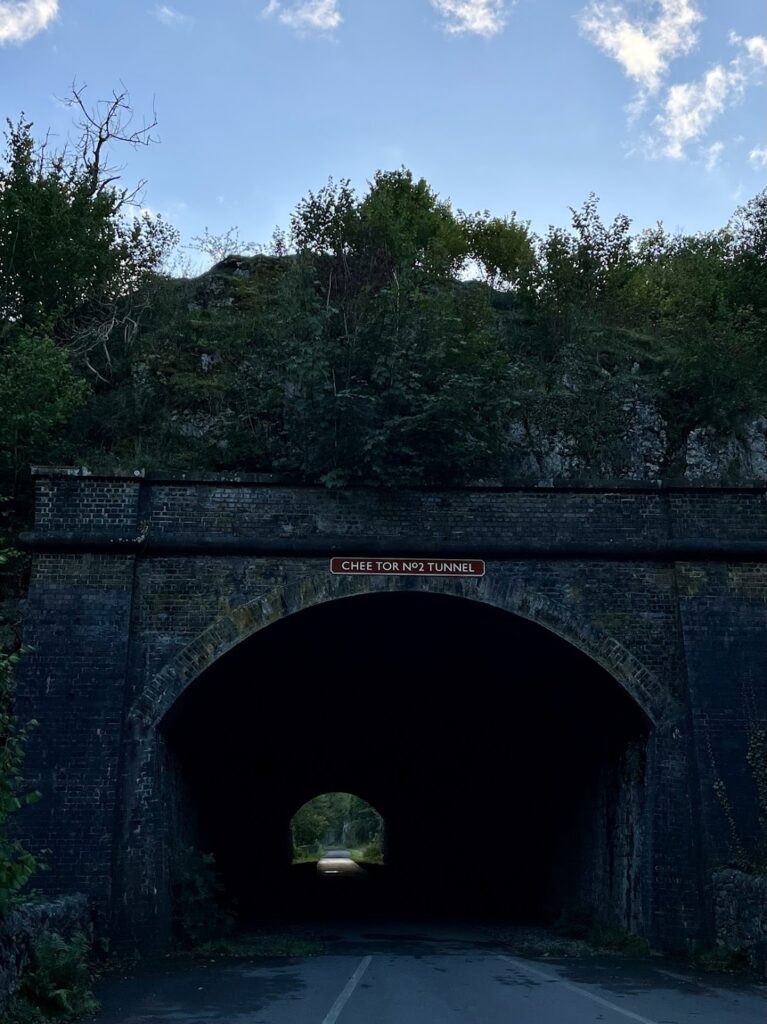

Across the Pond

British mums have a different vibe. There’s a looser family dynamic generally, which seems fine, and a sense that kids ought to entertain themselves a lot sooner. Every culture has its own ways. I’ve always appreciated the British phrase “she fell pregnant” implying that motherhood is some sort of disease, because aspects of pregnancy really do suck.

When Bear and I immigrated to join their dad, Bear was just turning 3 years old. Soon after, my mother-in-law complained to my husband that I was spoiling our not-yet-preschooler by playing with them too much.

My response was simply: “When, precisely, did this spoiling start? When Bear was a baby and toddler, when I was a single mum working full-time and finishing a degree?” My mothering, too, has been pretty survival-focused at times.

Still, I have plenty of British friends who clearly had children for reasons other than to complete housework.

British books have great mums, too: Agnes in Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet, for example. She seems to know her children on an almost supernatural level. “There is nothing more exquisite than her child.” Nazneen, fellow immigrant to Britain in Monica Ali’s Brick Lane, feels similar wonder for her baby. She can’t protect her children from everything but she loves them desperately.

Finally, Bernardine Evaristo’s Amma in Girl, Woman, Other. I think of her quote as I miss my own kid, now on the other side of the ocean with my mother and all the rest of my family.

“the house breathes differently when Yazz isn’t there

waiting for her to return and create some more noise and chaos

she hopes she comes home after university

most of them do these days, don’t they?

they can’t afford otherwise

Yazz can stay forever

really”

That sums things up for me. Who are your favourite literary mothers?