This Week’s Bit of String: Cabins in the woods

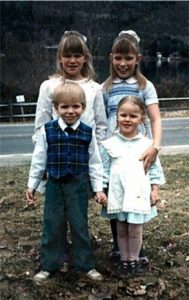

Beside a small but deep New Hampshire lake, opposite heavily forested hills framing each sunset, there’s a family resort with rustic woodland cabins, and a neighbouring converted farmhouse. That’s where I grew up—my parents rented part of the farmhouse, while my mother worked at the Lodge.

The lake and woods provided constant entertainment, but we were also fed a rich diet of stories and music. Bible stories, fairy tales, chapter books such as Heidi, Charlotte’s Web, The Borrowers, and more. I remember my father explaining A Midsummer Night’s Dream to me, very animated over who loves whom, his massive volume of Shakespeare’s works open tantalisingly between us when I was about three years old.

My parents also told us what went on in the world. Oppression in the USSR, famine in Africa, the Challenger. No matter how young we were, they couldn’t keep from us all the things that moved them.

We saw our first musical when I was five, a Prescott Park outdoor production in Portsmouth. It was The Music Man, and we were enchanted that song could be integral to storytelling. Add to that my dad’s devotion to Grateful Dead and other similar groups; we knew no topic was too big or small to warrant a song.

From all these sources, flocks of what ifs fluttered through our minds. Every time we packed to visit my grandparents, my sister and I pretended we were orphans escaping a workhouse. We created fortresses between cabins, looting junk piles for crockery and defensive chicken wire. During the off-season, Mom walked us through the woods, imagining we had to sneak past a different Disney villain at each cottage. Our stuffed animals served as characters when we acted out the Chronicles of Narnia and other dramas.

I don’t remember many limits proscribed to our ideas. It’s only fair; if you ensure your child knows all about crucifixion as a pre-schooler, you can’t really criticise them for occasionally manifesting morbid fascinations.

When I was about four, my mother let me use her typewriter to write stories. I never finished, unable to come up with a satisfactory ending (a problem which sometimes persists). But I was given space to try, mentally and practically.

So it wasn’t that surprising, while I planned my annual, too-brief visit to New Hampshire this summer, that my dad suggested, “What if we had a literary festival of our own, in our family?”

And lo, the First Annual Short Stuff Showcase came to pass.

More Than Stories

We moved away from the lake almost thirty years ago. But for a few glorious days last week we converged in its cottages, holding our Short Stuff Showcase in front of Playwood, the little recreational cabin that has witnessed many a ping pong tournament and rainy day video session.

It was the first time some of our partners saw our childhood home, and we were accompanied by my sister’s boyfriend’s family. His brother-in-law joined in with a striking poem about raising children to love a fearsome world, especially poignant as his toddler climbed around him with a heart-melting grin.

We opened with a trumpet-mouthpiece fanfare from my musician husband, who also contributed along with several others by keeping the small children occupied.

The programme continued with a variety of pieces from each of us: humorous and profound, original and recreated. My youngest sister enacted her favourite fairy tale with our old Cabbage Patch dolls, and my sister-in-law led us on the emotional roller coaster that was her diary from the summer she was ten.

My mother shared a song to convey her hope and faith for us, while my brother wrote a wonderful rhyme about establishing inner peace that can be reflected in art. I read out one of my lighter stories, “The Honorary Mothers League,” wanting to make everyone laugh. My dad mixed it up by both reading a silly song and then speaking about his appreciation for my mother.

At sixteen, my son might have been forgiven for eschewing the event, but the moment I’d mentioned it to him, he responded, “I’m in.” We’d discussed various ideas he could build on, and the night before, as we gathered round the hearth in our cabin, he scribbled a highly inventive tale about a bullfrog, a meerkat, and a crumple-horned snorkack. It was fun and also somewhat meta, defying the fourth wall.

My other sister had composed a poem about how we ourselves are the showcase, more than any small piece we produce, putting into beautiful verse a feeling that had warmed me throughout our gathering.

Living for a few years in an idyllic setting doesn’t equate to a completely idyllic childhood, and we’ve all had serious trials. There were plenty of instances, as we got older, when I’m sure our modes of self-expression caused our parents much more consternation than when I was four, pecking out a tale of a girl escaping a wolf.

And yet here we were, with beloved partners and children, with jobs we’re passionate about and the confidence to share. Our abilities to communicate and express ourselves through writing, and to empathise with others’ stories, have been indispensable bringing us to this point. We are the showcase.

Passing the Torch

When we weave stories, the ultimate tapestry will be partially comprised of bits of string stored since we were very small. I’ve already passed a bizarre combination of music, film, literature, cuisine, and holiday traditions to my son, and he’s freely adapted it. He must barely have been in school when we got him a binder to keep all his different story beginnings in.

Checking in at the Twittersphere, I found a few writer friends had much less family support than I did. Some families see writing as a futile or worthless endeavour. I’m impressed by people who overcome that initial discouragement to devote themselves to a pursuit that doesn’t frequently offer encouraging results.

On the other hand, the historian and writer Christine Caccipuoti Tweeted that her family was supportive “1000%. They had a policy of never saying no if I asked to buy books (as opposed to toys), allowed me to stay up all night if I was writing, left me alone to do so when I asked, and fostered my love of acquiring pretty notebooks to write in.” Fantastic, I could use that kind of support as an adult. How did your early childhood and family culture contribute to your writing life?

For more tips about supporting kids to become writers, there are a couple of articles here and here. There could be a Short Stuff Showcase in your future, too!