This Week’s Bit of String: The attention-seeking habits of adolescent male humans

Most Year 11s in our bottom-set class aren’t interested in the problems of the past. They’ve been taught about the workhouses and Thomas Malthus’s Poor Law of 1834, but our Trio of Fortitude just smirks over their A Christmas Carol essays when I prompt, “So why did Dickens write about Scrooge in that way? Why did he write this book?”

“Fame. Money,” they say.

And what surer way to earn those than write a book? I hear my fellow creatives laughing wryly at that.

There’s probably an element of projection here, assuming every adult from every time period will share the adolescents’ lust for money and fame. These are, after all, the same boys who’ve ridiculed me assuming my job is low-paid.

“You’ll never own a Lamborghini, Miss, so what is the point?”

As for fame, I don’t think these students crave it, but they do like a certain quantity of attention. The Year 10 boys have taken attention-seeking to new depths. They like to watch each other accuse staff of misconduct.

We squeeze through the crowded corridors to hear a boy shout, “Miss, did you just assault a minor?” One of our longest-serving, high-level TAs walked into a classroom to have a boy ask, grinning, “Didn’t I just see you chuck a pen at a student?” It happens with such frequency, we wondered if it was a TikTok trend. This particular group of boys get such a kick out of joining in to make bizarre claims.

Fame and Money

Attention-seeking is no fault, to my thinking. We all need attention, and I aim to give it to those I love without them needing to seek it. Ideally, we would know the students in our classes, even the ones not technically on the special needs register, well enough to cater to their personal interests and goals. But in a low-set Science class of thirty, many of the students with high need and low focus, while we’re trying to teach the entire GCSE curriculum, we’re mostly running around shushing and confiscating hazards.

Attention-seeking tactics, performances for peers, sometimes choke out opportunities to gain deeper, more constructive attention.

Obviously, when I write I do hope that certain pieces will gain favourable attention. Sometimes, in conversation, I prize making a witty riposte above empathy. Then I regret it after, even if I won a few gratifying laughs. Attention is great, but it’s not my raison d’etre.

My writing jobs in the last fortnight have consisted of preparations to feature as a Showcased Writer on another writer’s blog, and maintaining writing group correspondences and completing critiques, while also adding more to the new novel I’ve been working on. There’s a mix of promoting myself, others, and creating for the fun of it (which will hopefully one day appeal to others too).

Our Women Writers Network on Bluesky also hosted one of our Skychats, inviting other creatives to join in on the hashtag #WomenWritersNet. This month’s topic was the Writing Mindset and it was inspiring to listen to people’s thoughts about what this entails, and hammer out my own idea of it.

For me, a writing mindset is open to ideas, no matter how mundane the source, and is flexible in switching from gathering mode to the hard work of expanding an idea. My writing mindset is fed by such discussions with other creatives, and by taking in art of all forms–reading, listening to music, walking city streets–and yes, by affirmation.

Time Well Spent

By far, the most writing I do is in my daily scribbles. For 5.5 years, I’ve written on and about every single day, chronicling interactions and noting ideas. I sometimes worry about the amount of time this takes me, usually at least an hour each day.

Is the time I spend trying to preserve memories and thoughts distracting from the now? Or do my reflections enhance my present?

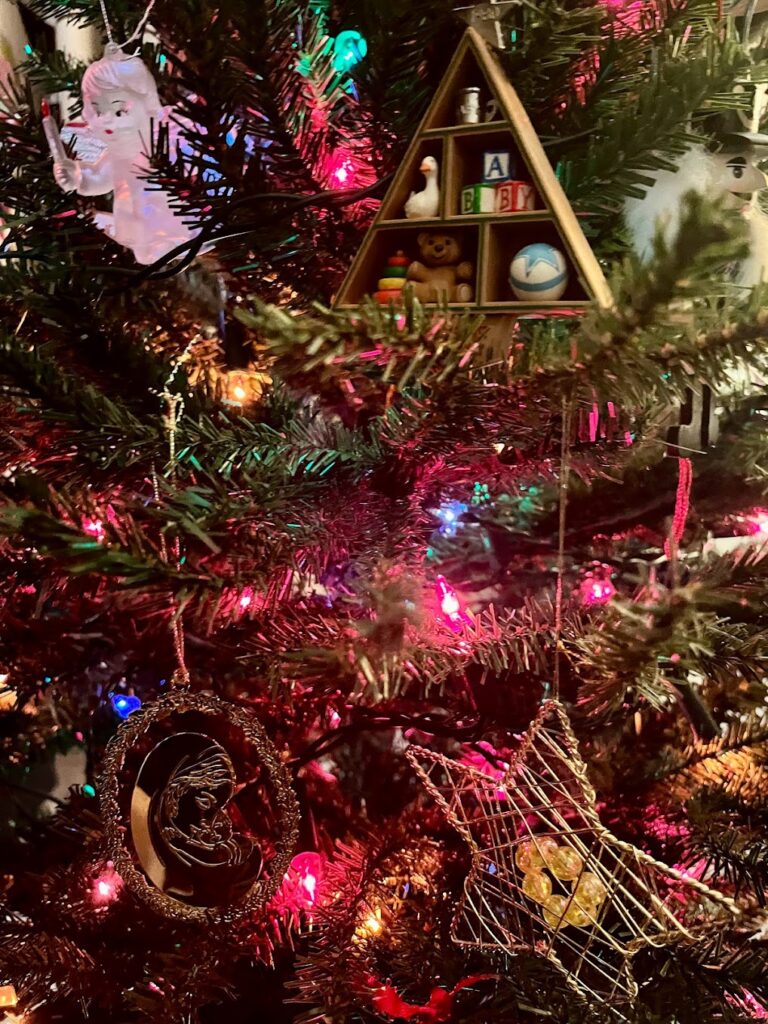

This week, as I prepare to visit my family in the US the instant half-term break begins, I’ve looked back through my notebooks. There are dozens of them now. I found the ones from each summer visit, and flipped through specifically to find each time we saw my Aunt Laurel, who passed away just weeks ago.

Since I’ll be helping my family in the wake of her loss, it fortified me tremendously to read family stories she told me that I’d recorded in my journal, and little bits of conversation, the ways we made each other laugh, how she’d reach up at least a foot over her head to hug my husband and call him “Sweetie.”

My journal also reminded me of her words: “It takes a lot of disasters to make a grown-up, or even to feel fully human.” That puts all the attention-seeking antics of young people in perspective, doesn’t it?

So, my favourite reason to write is to preserve love. To lay down a thread guiding me back to the best kind of attention, from the people dearest to me. It often works out that those people are the ones who give me strength and inspiration to keep creating.

Do you have people like that to fortify your writing mindset? How do you balance preserving relationships with gaining attention?