This Week’s Bit of String: Near-misses and resistant materials

“Miss, did you ever almost cause the death of a small child?” a year 10 boy asks casually as we sit on the high stools around a Design Technology table. Three boys with various tools and MDF fragments, me with my laptop and notebooks.

This is Resistant Materials. I know very little about CAD, woodwork or metalwork, but I’m supporting a student doing the GCSE. When I told my husband I’d be helping with Resistant Materials, he quipped, “Is that the course, or the students?”

Fair question. But I’ve clearly won some trust. The boy who’s asked this surprising question explains to me that he was once on a ferris wheel with a friend, and her shoe fell off and almost hit a toddler on the ground. Hence, he feels he was beside someone who almost accidentally caused the death of a small child.

Story ideas pivot on crucial moments like the one he mentioned. A slight change in breeze, an incremental rise or fall in the Big Wheel, and the shoe might have hit. I noted the exchange with the Year 10 boy and preliminary thoughts about the alternate scenarios in my daily scribbles, ready for half-term when I have a few free hours to sit, and wrestle out my first new story of the year. I’ll have my latest novel edits all typed up by then.

Exploring Options

Around the time the Resistant Materials boy mentioned his anecdote, I was reading through a literary magazine called Story. It’s based in the US, and I discovered it because I was looking for submission possibilities and Googled “short story magazine.” Sometimes we forget to keep things simple; we look through comprehensive listings of publications and deadlines and fret over word counts… This was more a case of “ask and you shall receive.”

There were some great stories in this issue. My favourite was about a group of boys and their scout leader who got trapped in a cave for several days. The dynamic among the boys before, during, and after was fascinatingly written. It made me realise–and again this sounds SO obvious but it’s another thing that I lose sight of now and then–we get to make stuff up.

I’m pretty sure the writer hadn’t been stuck in a cave or been close to someone who was. But they did a great job making up the scenario and tracking its impacts. I’m going to do that too, I thought. Make something up.

I tend to be a bit timid with my ideas, whether it’s from actual fear or more likely, lack of mental energy. Starting from scratch is EFFORT, to borrow the ultimate disparaging statement from my students. That’s why it can be useful to begin with a memory, with a favourite setting or even person, or with a retelling, a twist on something old.

What About the Future?

Lately, I’ve indulged in inventing future scenarios. If my imagination is slightly inhibited regarding stories, I severely limit it when considering how real life could turn out. I’ve done this from a young age, to avoid disappointment. I specifically remember preparing for my 8th birthday, to be celebrated at Chuck E Cheese’s, something I’d wanted for years. Rides! Games! Pizza! I’d wanted it, but wouldn’t allow myself to picture it, because that would risk building expectations.

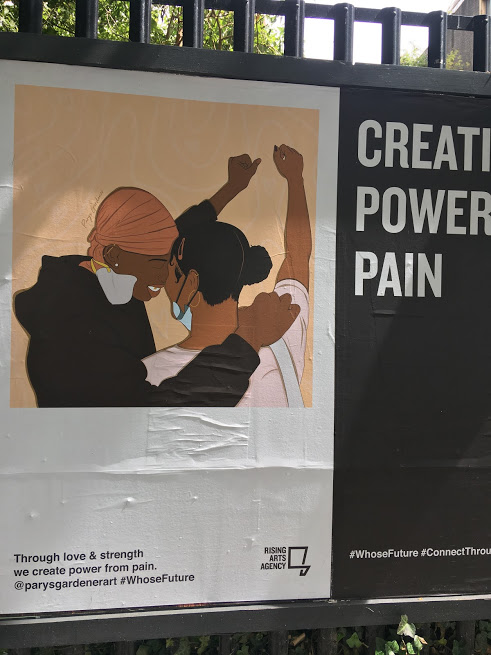

If we’re tuned into the world, and we have an ounce of empathy, it can’t escape our notice that we’re clinging to some privilege. Whatever tough times we’ve had, billions in the world are substantially worse off. My husband and I remark to each other sometimes about the Event, an imaginary but tacitly half-expected reversal of world fortunes.

“This would be a strategic location in the Event,” he says when we take in hilltop views on a hike.

“For the Event,” I say when I add to the ranks of canned goods in the cupboard.

But it’s also possible that amazing things will happen in the future. You know, on occasion. Struggling to sleep with exam stress on behalf of my students recently, I started imagining what, for example, our 30th or 40th anniversary might look like, having just celebrated our 20th.

Maybe we will be surrounded by family next time, instead of on our own. There could be a new generation of children on the scene, and though another decade could see further health complications for my parents, I imagined my own kiddo helping to ensure they’re looked after, and this brought comfort.

We can’t get attached to any single projection of the future. But envisioning positives—perhaps especially in the form of small, everyday details—is a new bravery for me. Part of appreciating what I have means letting go of my expectation of disappointment. And if events look to go in a different direction, then I’ll just make up new hopes.

How do you keep sight of the freedom to make things up?