This Week’s Bit of String: Exclamation points and everything

Disappointment stirs among some of the A-Level Creative Media students. One of their teachers has been unwell for several weeks, and they miss her.

“She’s STILL not back!” This statement greeted me on Monday morning. Wide-eyed, the Year 12 girl explains, “And we sent her a get well card last week, so it’s just rude not to mind it. We put an exclamation point on and everything. That makes it a COMMAND.”

She’s half-joking, but I suspect they did hope their greeting would have strong restorative powers. It made me think a bit about power dynamics. When we ask someone–or even tell someone–to do something, we may think we’re wielding control, but in a way we are giving it away because we rely on the other person to comply.

Back to the Roots

Interestingly, the word “command” is rooted in Latin for to order, but also to entrust. That’s reflected, I suppose, in our English phrasing: To give a command. We extend an order to another party, but it’s then up to them if they take it. The power is not entirely with the person giving the commands.

This sort of control exchange is on my mind because… it’s submission time again. I only have a limited number of short stories, and I’ve thrillingly just had one accepted. (It’s super fun and you can read it here!) My semi-depraved brain only rejoiced in this for a few hours before starting to panic that this means I don’t have anything currently in the Out on Submission column of my writing spreadsheet.

It’s time to start all over again: researching publications and competitions, editing and wondering if I’m going in the right direction at all, amending format to the exact requirements, drafting cover letters, etc. And then, waiting, very possibly getting rejected, and then repeating the whole process.

You know the drill.

Putting the “Mission” in Submission

To psych myself up for this (and maybe I can psych some of you other writers up in the process!), I looked into the etymology of the word “submit.” There are a lot of connotations to this word: religious, marital, and so on. Indeed, the Latin root means just what you might respect: “to yield, lower, let down, put under, reduce.” It does feel sometimes as if, when we submit our work in hopes of publication, we are prostrating ourselves before an almighty authority.

But separating out the sub- (under) from the -mit gives the idea more nuance. We forget sometimes how that second half of the word means to send out, to release, to bestow. While submitting our work does leave us vulnerable, it’s the primary route available in order to share our gifts with the world.

Sure, it would be nice if acceptance were guaranteed. I remember finding it really tough to convey when my child was little that just because they used their newly-learned manners, it didn’t mean they’d get what they asked for each time. “But I said please!” they might insist, when a request to stay up later or to have more “clockit” (chocolate) was refused. As John Green wrote in The Fault in Our Stars, “The world is not a wish-granting factory.”

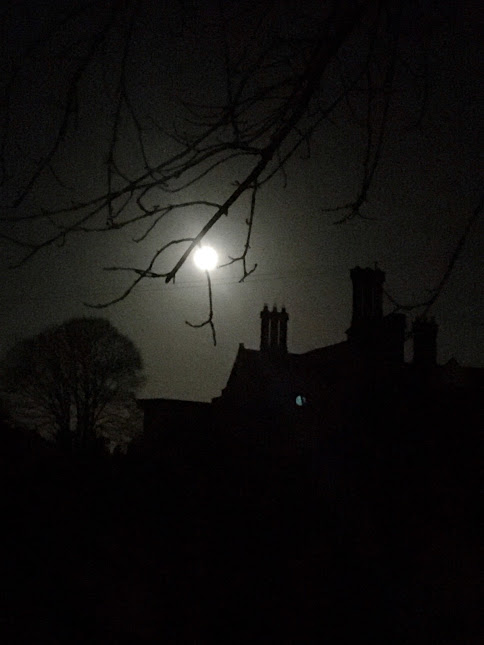

As writers and artists, often particularly sensitive and empathetic people, our mission tends to be deeper than getting recognition for ourselves (although given the hard work we put in, that’s definitely part of it). Maybe we want to illuminate darkness, amplify silenced voices, add beauty to the world, or make readers laugh. That’s the mission, it’s why we send forth our work into the world, and our successes are worth the many failures.

How do you encourage yourself when it’s submission time?