This Week’s Bit of String: Tiny pencil people

When I began writing my first ever novel at the age of eleven, I enacted it with an entire town’s worth of pencils.

Tall ones were adults, and smaller ones were kids. Yellow ones were men; coloured ones were women. You can see the sense in this, right?

I’d divided every shelf in my bedroom, one third of my drawers and the floor of my closet into little cubbies representing each building in the town, decorated with unique postage stamp pictures on the walls. The pencils had furniture—stub pencil babies slept in milkweed-pod cradles—and in some cases, even scraps of clothing sellotaped on.

For years pencils had been speaking their personalities to me. The chewed, battle-scarred ones and the prissy, fine-tipped ones and the fluorescent, too-trendy ones. Some of the citizens in my story-ville were carefully nursed survivors of first grade, when my little rural town sent us to a tottering two-room schoolhouse. We sat at ancient desks with ink pot holes in them, and the boy in front of me used to twist round and drop my beloved pencils through the hole. I sometimes wonder what happened to that boy. With the surname Dyke, he must have had an awful time in his later school years.

Even as adults, when we get swept up in a story idea, everything around us reflects aspects of it back at our infatuated brains. Have you ever noticed that? But I’ve been so busy lately, it’s been a while since I succumbed to such flights of fancy. I miss it. How do we ensure kid-high levels of imaginative activity when we’re getting a tonne of adulting done, too?

Twitter-pated

I turned to Twitter (which I’ve also been neglecting due to time constraints) for suggestions on maintaining good creative habits and keeping the dreams alive.

Some of these ideas overlap with the tips I gave back when I was adjusting to full-time work. Adjusting implies a process with an end, but I’m not sure I’ve completely figured out the balance. Does anybody? So reminders are all good.

Firstly, don’t stop writing. Even if we are taking a break between projects, we should keep scribbling observations and thoughts (bits of string…). Writer and editor Emma Cummins reminded me to make a habit of writing little and often. Because we all know what happens when we have a cool idea, and try to stash it in a corner of our ever-churning minds while we rush off to do the next thing.

You can find Emma’s website here–she particularly focuses on reviews of art and cinema, which is perfect because taking in aspects of culture outside our own creations helps us develop new ideas, too.

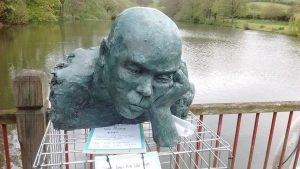

Where else can we find things to write down? Creative writing teacher Stephen Tuffin suggests hanging out in graveyards, or accompanying someone to the shops without shopping yourself. (For some of his other, uniquely flavourful thoughts on writing, check out his blog here.) I remember seeing a 19th century gravestone for a child, with the verse ‘God’s will be done’ carved on it. And I wondered, did the parents agree on that resigned sentiment? Was it someone else’s idea entirely? Did they argue over what their faith meant in the face of such terrible loss? Given that I encountered that ‘bit of string’ over a decade ago, I guess cemeteries can make quite a lasting impression on the imagination.

Or follow Stephanie Hutton’s lead and snap up some vintage postcards from eBay or even a charity shop. Not only do you have the pictures to prompt you with story ideas, but each postcard message opens worlds of possibilities, in what’s said and perhaps what’s not said. Stephanie is part of The Writing Kiln, which aims to inspire confidence in budding writers. Have a look at their website here.

Vlada Poladyan advises putting sleep to use, to mesmerise and spur the imagination. She cites Stephen King’s nonfiction book On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft for teaching her a routine for creative sleep. It’s been several years since I read On Writing, and it’s clearly time to check it out again.

Finally, Shannon Ferretti points out, ‘Daydreaming is important and a good use of time, [so] I bury my worries way down and play in make-believe lands instead.’ Part of getting back our imaginations is giving ourselves permission to daydream. We must remember that as writers it’s kind of our job to fantasise and create.

But we also must avoid feeling that every daydream should serve a marketable storyline. That’s been my problem. Being short on time, I get to thinking every idea has to count toward some ultimate writerly goal. I need to remember that every bit of string has value, even if it doesn’t lead to a beginning, middle, and end.

Every random exchange witnessed, every anecdote passed on, better informs our sense of the world and humanity. And every silly idea can lift us beyond that. So that’s worthwhile, isn’t it?