This Week’s Bit of String: Crying over cats

‘Miss?’ the Year Eleven boy asked me, tossing his carefully sleeked hair without looking up from the doodled serpents invading his Science BTEC exercise book. ‘Do you ever start randomly crying while you’re petting your cat, because you wish so much they could talk to you?’

I don’t think it’s ever brought me to tears, even when I was sixteen myself, but I definitely used to look in pet cats’ eyes and sense much present in them that we, their humans, missed.

The boy’s question brought to mind a passage from Muriel Barberry’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog. Renee refers to her ‘appreciation’ for her tenants’ cocker spaniel as: ‘that state of grace attained when one’s feelings are immediately accessible another creatures.’

We now have only guinea pigs as pets, but their feelings are pretty darn accessible. They’re an important if timid part of our family, an affectionate interest uniting us as our son gets older. And if anyone doubts that animals are sentient, I defy them to look at a guinea pig, any guinea pig, and not be struck by the chronic consternation on their faces. It’s as if they’re constantly in dire need of food but always expecting to be disappointed.

Since animals cause us to reflect on what makes us alive, what makes us sentient (to use a rather unattractive, clinical-sounding word), and they bring us joy and unity—isn’t it right they should feature in literature?

Animal Voices

It’s easy to find animals in the fantasy genre. The dragons of Pern, the owls and thestrals of Hogwarts, the daemons of Lyra’s Oxford, the Noisy animals of New World in Patrick Ness’s Chaos Walking series (oh, Manchee!)

So too they should be present in mainstream literature, sincewhen we write we attempt to reflect and learn from real life. Certainly animals have served as set pieces and symbols in literature since Homer told of Circe’s pigs and Polyphemus’ sheep. But in using them only as such, do we devalue their contributions to our lives?

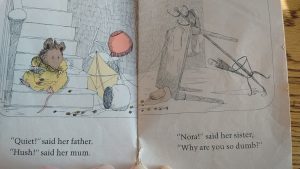

There’s the pigeon offering occasional commentary in Pigeon English, and the freed parrot in Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue. The parrot gets a chapter of his own: one long, continuous sentence. His thoughts fly free as he leaves the home he knew for decades, after his owner’s death. It’s nice to get these extra, imagined perspectives, but by making animal characters simply witnesses to the humans’ folly, they remain a little flat.

A great example of using animals realistically yet appreciatively is Marina Lewycka’s Two Caravans. Her novel about immigrants in the UK encompasses many points of view, including a dog. Different characters rate each other based on their respective reactions to Dog, and he leaps in to save the day at the end.

The novel also features scenes in a chicken-packing factory, which convinced me to buy only free-range products ever after. Her depiction linked callous attitudes about animals to abuse and exploitation of migrant workers. It should hardly have been surprising, but it had a somewhat revelatory effect on me.

Animal Roles

Although these authors have gone to great imaginary lengths to use animals as characters and assign voices to them, there are other ways to integrate our furry (or feathery or scaly) friends. Why is it so rare to encounter human characters who own pets? Allusions to a pet can serve as useful shortcuts establishing character. Are they a dog person, a cat person, a horse person, maybe something more unusual like a snake person?

In my novel The Wrong Ten Seconds, treatment of a dog catalyses the action. Pets are a central part of characters’ lives. Introducing one of the protagonists, Lydia, I described her car:

‘The cluttered Fiesta—Mabel—smelled of takeaway curry and chips, cat litter bought in bulk, and hand sanitiser.’

Beyond representing personality traits of their owners, including pets in stories gives humans opportunity for insight. Lydia is self-aware enough to know that she needs her cat, Slim Shady, more than he needs her. She recognises his purr doesn’t always convey happiness, but sometimes cloaks fear. The purr indicates to her:

‘You only get away with this because I in my benevolence allow it.’

Animals at the Beginning

In my current novel, about Eve and the (presumed) first family of humans, animals have an even bigger role. As much as Eve and Adam’s lives changed on their expulsion from Eden, think what it meant for the animals! Through no fault of their own, they had to leave paradise as well, and were thence forward seen as fair game. Literally.

Surely humans didn’t go straight from discovering wildlife wonders in Eden, to wearing animal hides and eating meat outside its walls. The sudden need to provide for themselves would change things, but it would not be a comfortable adjustment. Tension grows between Eve and Adam when he starts out eating fish:

‘What’s next, killing cows? Lions, lambs? You could roast one of the angels.’

‘Don’t speak to me like that, woman! I’m not the one who ever sought something I wasn’t supposed to take.’

The way each character relates to animals represents and colours the way they relate to others. Adam tells himself he has dominion over the animals, but in God’s curse on Eve, she’s been told her husband will have dominion over her. Does that make her equal to the animals? This is just one reason she has a keen interest in how he treats them.

Further, they have to wonder about God’s purpose in creating themselves and the animals (which, for this work, I’m imagining He did; see my previous post on working with incredible premises). If God is willing for them to dispatch with the animals so easily, what does this say about their own mortality?

It’s like Sirius Black said (somewhat ironically, given his later treatment of his own house-elf) in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, ‘If you want to know what a man’s like, take a good look at how he treats his inferiors, not his equals.’