This Week’s Bit of String: Trying to catch fish

I encountered a heron at the canal yesterday. First he was opposite me, silver-grey shoulders down and white neck straight, alert to passing humans rather than fish. He took off as I neared, his wings so great only a few ponderous beats made him disappear.

Then I saw him further on, bringing his sharp yellow beak close enough to the water to kiss his reflection. But something put him off—the cat stalking blackbirds on the bank behind him, perhaps, or the mandarin duck couple landing on the water.

The heron swooped across the canal and stationed himself on the riverbank instead. I watched him creep closer on his stick-thin legs, and lean down to check for fish. Then I pushed myself on for a couple of miles before work, wondering if the cyclists who soon passed me scared the heron off again with no breakfast.

Hurrying back I found myself right next to the heron. He’d decided, for some reason, to take a canal spot by the path but couldn’t tear his gaze from his surroundings long enough to lower his beak into the water.

He was too distracted by fear of predators to catch his own prey, and I wondered if we’re the same sometimes. Do we take risks for gains but end up so crippled by fear that we can’t act on our plans?

The Paralysis

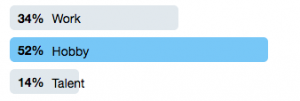

Pulling together a successful writing career requires gripping several threads at once:

We have to actually write decent stuff (and it’s wicked hard).

We have to learn how to write decent stuff by reading decent stuff (which can be dangerously addictive).

We have to remind people on social media that we’re writing decent stuff, and we want to be decent human beings too, so we’ll spend time supporting other people who are writing decent stuff (and there’s some very decent writerly stuff out there, so this can be addictive too).

Finally, we have to get our decent stuff published or broadcast or featured somewhere, preferably on a semi-regular basis. This means scouring publications and, again, social media for competitions and literary magazines. It means querying agents and familiarising ourselves with rejection.

A lot of us handle all this while raising a family and working a full-time job. It gets seriously overwhelming. There are moments when I find myself motionless, apart from my eyes flicking down the Facebook or Twitter feed, watching other writers claim success while feeling as if I don’t dare lower my beak and take a brash snap at a fleeting competition deadline.

The Perch

This week I made a longlist but got no further, while seemingly everyone I know swooped to greater heights. I scanned the short list but caught nothing. I said ‘fuck’ several times under my breath. I got on with my day at the office but felt frozen inside.

Then ideas started swimming past. I reminded myself to move, to seek new vantage points and new submission opportunities. To catch something, we have to dip our beaks. We have to stop reading everyone else’s elated Twitter reactions (but Like them anyway, because we’re decent human beings after all).

I went for a walk in the local park, searching for ducklings to cheer me up. I didn’t find any cute flufflets that day, but I did spot a one-legged pigeon hobbling around to the grudging admiration of some black-clad teenagers. And I saw a robin in a monkey puzzle tree.

I suppose if you’re quite small, big spikes don’t matter. I couldn’t see the robin’s feet, but I could see his proudly puffed rusty chest and sharply aware black eyes. I imagined his skinny toes curled around individual monkey puzzle thorns.

So it’s time to remember that having to start over brings the privilege of choosing a new path. There are plenty of spots to try, plenty of fish for us all to catch—all we have to do is dive.