This Week’s Bit of String: Milkweed cradles and postage stamp paintings

As a kid, I never threw away a pencil. Each had its own personality, as I used them up to lengths which would correspond with their ages. From assigning names and ages to pencil fragments and little boxy erasers in first grade, I progressed to grouping them in families.

By the time I got my own room at age eleven, I was ready with cardboard shelves and my entire top drawer. I made a town for my pencil families. They had scrap blankets and I would put plastic sheets from envelope windows to serve as windows cut in the cardboard. I saved milkweed pods as cradles for the shortest pencil nubs, and padded the bottoms with satiny milkweed tassels. I peeled stamps off letters and stuck them up as paintings in the pencils’ houses, reflecting the residents’ professions and talents.

Naturally, you don’t grow a whole town in your bedroom without the relevant paperwork and a whole lot of backstory. My town was populated by people fleeing the nazis; it was hidden in the Polish woods. In seventh grade, I wrote a few hundred pages on the refugees’ adventures.

I tracked names and ages on an extra-long sheet of yellow legal paper: my census. I remember misplacing it one evening and wandering through the house saying, “I lost my census!” It was easily misheard as me losing my senses.

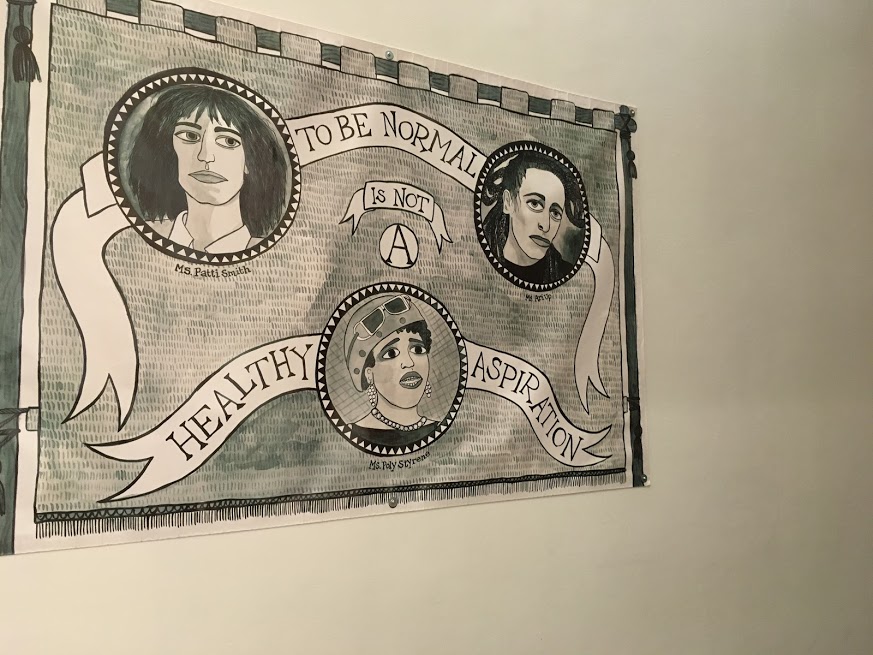

I’ve always loved a book with a map or a cast list at the beginning. Any visible evidence for the world I’m about to enter is most welcome. We had a poster map of Narnia up in our house when I was little. Did you find supplemental artefacts for any of your favourite stories?

Distraction or Inspiration

Creating meticulous artefacts to go along with our works in progress can be an essential step in story-writing. I often curate a soundtrack of theme songs to keep me going. For my Eve novel, I wrote out genealogies and calculated the exponential growth of the population as generations progressed.

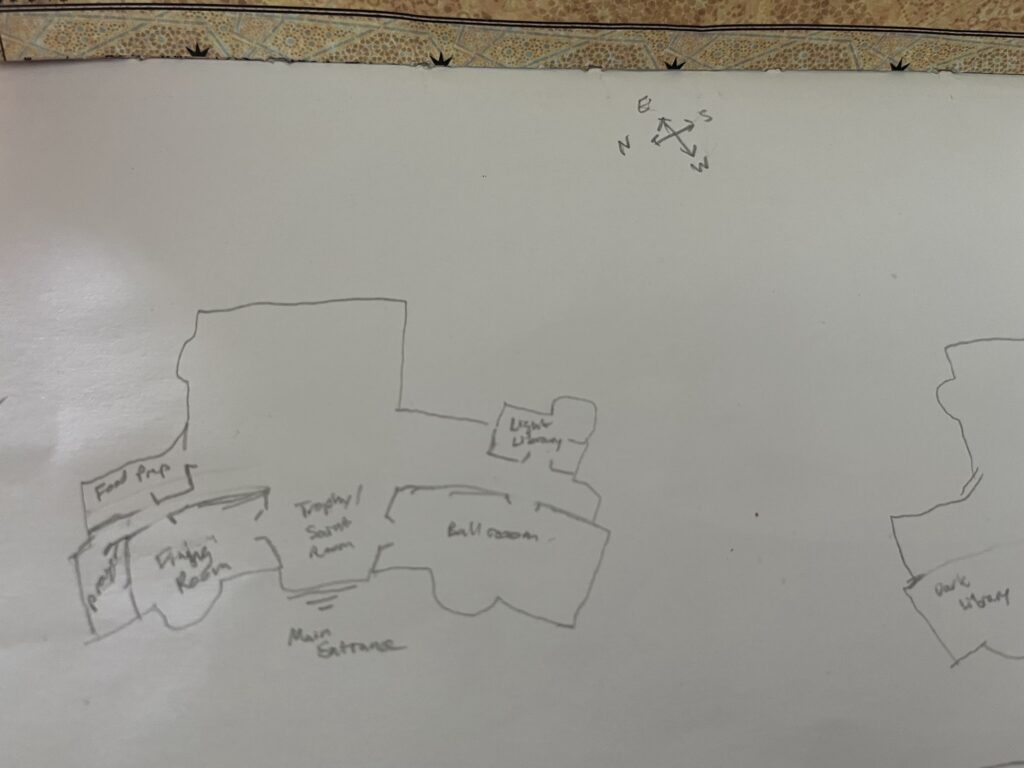

In the early stages of writing a new novel, I’ve been creating detailed character profiles, and an aristocratic family history as well as highlights of a contemporary artist’s catalogue. I think the novel will take place in a half-finished gothic mansion, so I am inventing the history of the house as well as sketching a sort of floor plan. I’ve never done this before and it’s quite fun. How big shall I make the library? What view shall I give it?

I need to know how things look and where everyone is within the house in order to chart the action, so these things are important. They’re also, in a way, a bit easier than studying the character profiles and considering how they might extend into novel-length trajectories. For me, the hardest part of writing a novel is ensuring there’s a clear, engagingly-paced beginning, middle, and end. Making extra planning documents and visual representations puts off that moment when I have to figure out whether this idea really has the stuff of books.

Useful Daydreams

As writers, we can be prone to fantasies which we’ll never bother writing down. It may sound indulgent to spend time on bits and pieces which will remain in the background. Maybe they’re just decorations for the more integral structure of the plot.

But writing a novel is very hard work. It might go better if we like our characters and scenes enough to while away hours imagining them. We’ll be spending a lot of time with them anyway.

For me, the supplementary bits I do become more than planning tools. The soundtracks I piece together, for example, catapult me at an accelerated rate into my character’s mindset and the mood of a scene. I haven’t developed a soundtrack yet for my upcoming work-in-progress and I’m looking forward to listening and experimenting with what might fit.

As for the paper artefacts, the blueprints and maps and family trees, these ground me in the story rather than just in the plot. In the adult world we still desperately need those fragments which bring the imaginary to life. These are the threads we can snatch–little baby pencil stubs, fantastical maps, fraught genealogies–to connect us to new worlds.

What kinds of artefacts do you use to accompany your creations?