This Week’s Bit of String: That ship has sailed

There’s a house I walk past on my early morning hike each day, with a round window like a porthole under the steep roof’s apex. The pane covering it boasted a stained glass sailing ship.

Only it’s not there anymore. I noticed recently, the porthole now has normal glass. Nice glass, with a whorly navel in its centre, but it’s not an adventuring ship. I did not approve this change.

During lockdown one gets attached to certain things. While unable to leave town for months on end, the sights on my limited range of local hikes became my safety network.

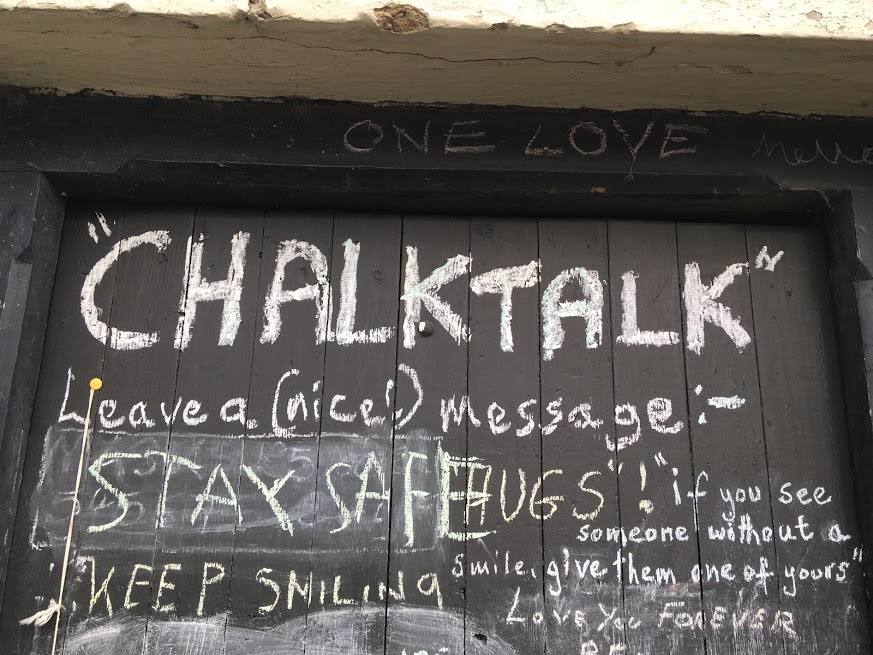

Blossoms and blackbirds, shop displays and creeping cats, the church rubbish bin with a fish symbol painted on it just in case the name and location aren’t identity enough. Footbridges and milk deliveries. The man with two huskies who wears a neon vest asking for space, and always smiles Good Morning when I give it to him. The young guy who strides down to the construction depot at the new housing estate and takes position outside the gates to aim a thermometer at the foreheads of entering labourers. The patched and re-patched bit of pavement which my son always said looks like a guitar, insisting we make suitable sound effects every time we walked over it.

So it shook me to realise a little mainstay of mine, something my gaze sought out while I hustled uphill from town, had disappeared. When did I see it last? What if the window was changed a while ago and I didn’t notice?

Missed Signals

I’m not sure if monotony is better or worse for noticing things. We might notice the slightest change, or we might have started tuning out. Even now that lockdown’s over, I use the same 3.8 mile route most mornings because I don’t have to expend energy on decisions.

We need choices sometimes, though; to confront us into consciousness. A couple of weeks ago, one of our guinea pigs got sick, after 4.5 years with us. After multiple attempts to dropper water into him, we took him to the vet, and sadly George died there in the night. Had I noticed his discomfort too late? Should I have put him through the trauma of a vet visit earlier? You can bet we’ve been watching his brother extra carefully. I’m not sure Fred is pleased with the spotlight; he prefers food to affection.

I assume other people struggle as I do to be more present, less dulled by the daily grind. As parents we’ll always be trying to catch up with what we miss, and as writers it can be even harder to notice things, even while we’re the ones who should be super observant.

Taking Roll Call

The thing is, writers have an observing, idea-gathering mode, but also a developing mode. When we notice something that snags our interest, our body moves on but our mind is snared in what ifs, and character-building. While it’s nice to be consumed, to have that momentum, we don’t want to miss too much.

Here’s what I’ve been reminding myself to stop and look out for, even while in the midst of plot problem-solving:

- Multi-sensory check. Every now and then pause and concoct a quick description for each smell, sound, sight, taste and texture around you.

- Revel in the wrong. I recently saw a typo in a Missing Person notice, describing a “balding man with a bear and glasses.” This transformed a sober paragraph about a man with facial hair to an imagined adventure with an ursine companion, and my imagination hadn’t had such fun in a long while.

- All creatures great and small. A ladybird straying across the work desk, snails curled around lavender stalks, their shells listing blissfully sideways, judgmental rooks and feline drama queens. It’s fun to make inferences about all their behaviours.

- Sift through the remains. Any found object in your travels could tell a story, from a dropped shoe or stuffed animal to a grocery list. A badly repaired square of pavement, allegedly guitar-shaped, brings me happy memories of walks with my son, so truly inspiration can be anywhere.

- Shameless use of prompts. Every day I try to come up with, for example, a sky description. Or a description of something in relation to the sky. This derives from when I used to use a sentence starter, “The sky today…” and it became habit to look out for the sky and how to portray it.

- Keep an eye on your people. I have kept up with daily journal scribbles, primarily to leave myself reminders of thoughts and experiences shared with my family. For years I didn’t want to keep a journal, reserving any precious writing time for “real work,” pieces that might be published. Now, I’m so glad I recorded some interactions. These are the last things I’d want to miss.

What have you been noticing lately? Do you have any suggestions on how to keep observational skills sharp and make the most of the moment?