This Week’s Bit of String: A dark and stormy night

One rainy evening out of several rainy evenings this week, our cat Oberon got restless. He was hanging around the hallway, so I opened the front door in case he wanted to go out.

Named for the prince of the fairies, Obie does have a microchip-activated catflap in our double-glazed back door. It’s complete with fixed metal platforms in and outside the door for him to step up to the opening and then down, most daintily. Whenever possible, though, he naturally prefers a door to be opened for him.

When I opened the front door that night, exposing the wind and rain, Obie hissed immediately. That’s a no, then.

He lives in hope that the front door, actually at the driveway side of our semi-detached house, will reveal a different world from the one he sees out the back door into the garden, or the front windows onto the front garden and the cul-de-sac.

For us humans, opening our own front door rarely brings surprises. We expect most deliveries and don’t receive many guests. With Remembrance Day just passed, I consider the days when a knock at the door could bring devastating news. Now we have much tinier rectangles that do that for us.

Story Portals

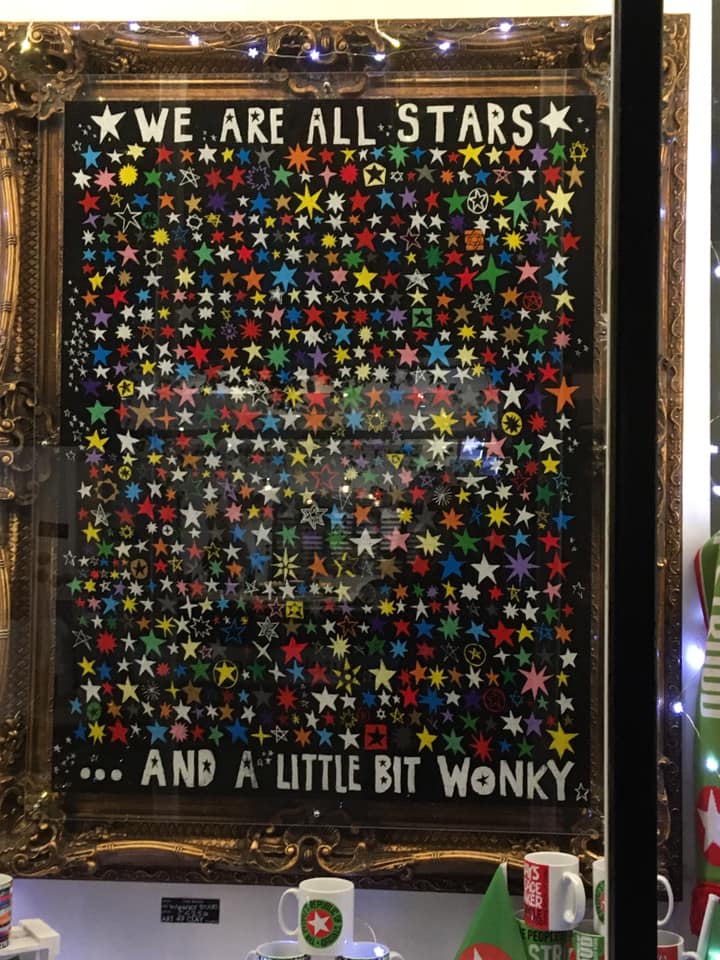

Last Saturday, before the sun retired into indefinite hibernation, I spent the day wandering around Stroud for the Book Festival there. I went to Alice Jolly’s book launch for her new novel, The Matchbox Girl. It sounds excellent, a story told by an imagined adolescent neurodivergent girl who collects matchboxes and spends time in the Vienna Children’s Hospital, where she gets to know Dr. Asperger.

Jolly told us about the Children’s Hospital, and its workers who resisted categorising children, viewed each patient as gifted, and simply believed the deficiency lay in adults who hadn’t learned to understand a child’s differences yet.

Mock exams started this week for my poor SEN students, so let me tell you, that sounds pretty awesome.

Unfortunately, The Matchbox Girl is set in 1934 and the ensuing years. So, things didn’t go so well in the lovely Vienna Children’s Hospital after a while. Dr. Asperger was revealed in this century to have collaborated disastrously with the Nazis.

Jolly explained that she was researching Dr. Asperger and the hospital, but didn’t know how to write a novel about it all until she had the idea of the matchbox-collecting Adelheid.

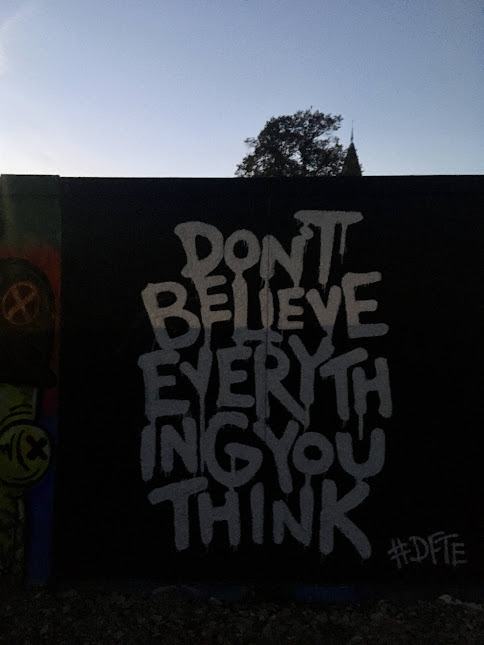

She said, “When writing a novel, you must never go in through the front door. You must find a way in the back.”

This edict pierced me. I’m always seeking to improve my craft and when a talented writer, who teaches Creative Writing at Oxford no less, issues a proclamation about how stories work, I immediately inventory everything I ever wrote. I suspect I’m not the only one?

Anyway, I was thinking, “What is the front door to each of my individual projects, and which is the back? Have I been heavy-handed and just crashed through the front, is that my problem? Why don’t I immediately understand what my novel’s front door is, is that my problem?”

Head and Heart

I meant to submit my novel The Gospel of Eve to more publishers and agents this year. But I was wrapping up an edit and more dauntingly, a synopsis rewrite, when I became so busy with critiques and a new project and work and family, I sort of forgot. That’s a major goal for 2026.

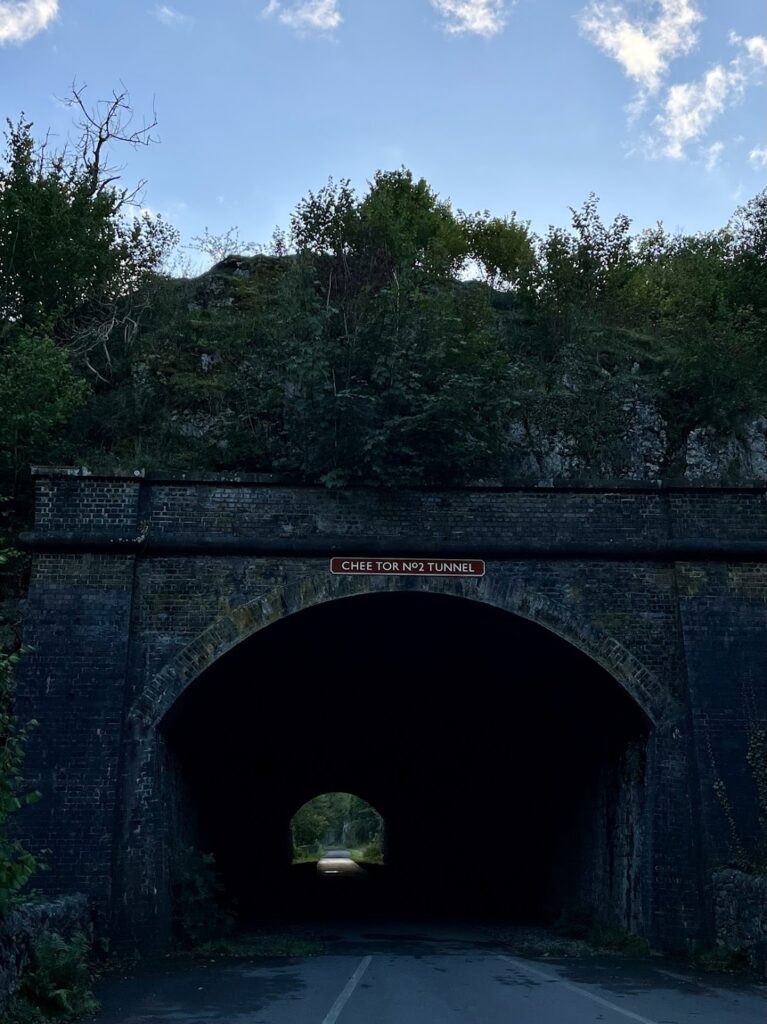

But Eve in herself is like a pre-fabricated back door, isn’t she, relegated as such for millennia? In my new project, I suppose the front door is the whole relentless mess of trying to appear good, while the back door is the comparatively straightforward (but still quite messy) task of fixing up a New England resort and cabins. Each banging cottage door reveals not just the renovations needed inside, but further internal turmoil for the new owners resulting from past relationships.

While at Stroud Book Festival, I also attended an interview with Elif Shafak regarding her latest novel, There are Rivers in the Sky. I’m excited to read this book as well. It spans history through a single drop of rain and incorporates the epic Gilgamesh poem.

Elif Shafak is passionate and graceful, and she spoke about the difference between information, which we have in overabundance; knowledge, which requires sustained commitment; and wisdom, which engages the heart.

I don’t want to worry so much about front doors and back doors and such, so that the heart of my project goes the way of the sun recently, obscured by my deluge of thoughts. It’s been such a long time since I actually started writing a novel from scratch—my Eve novel started as a short story—that I’m constantly questioning myself. Were my previous drafts this rough?

But after receiving very positive feedback about the first 3000 words, I started to feel better. It takes time to find a story’s heart, front door, and back door. Now that I know someone wants to read more, that gives me strength to keep discovering.

Have you been to any literature festivals this year? What great books have you discovered, and what insights did you gain into your own creative work?