This Week’s Bit of String: Practising Descriptions

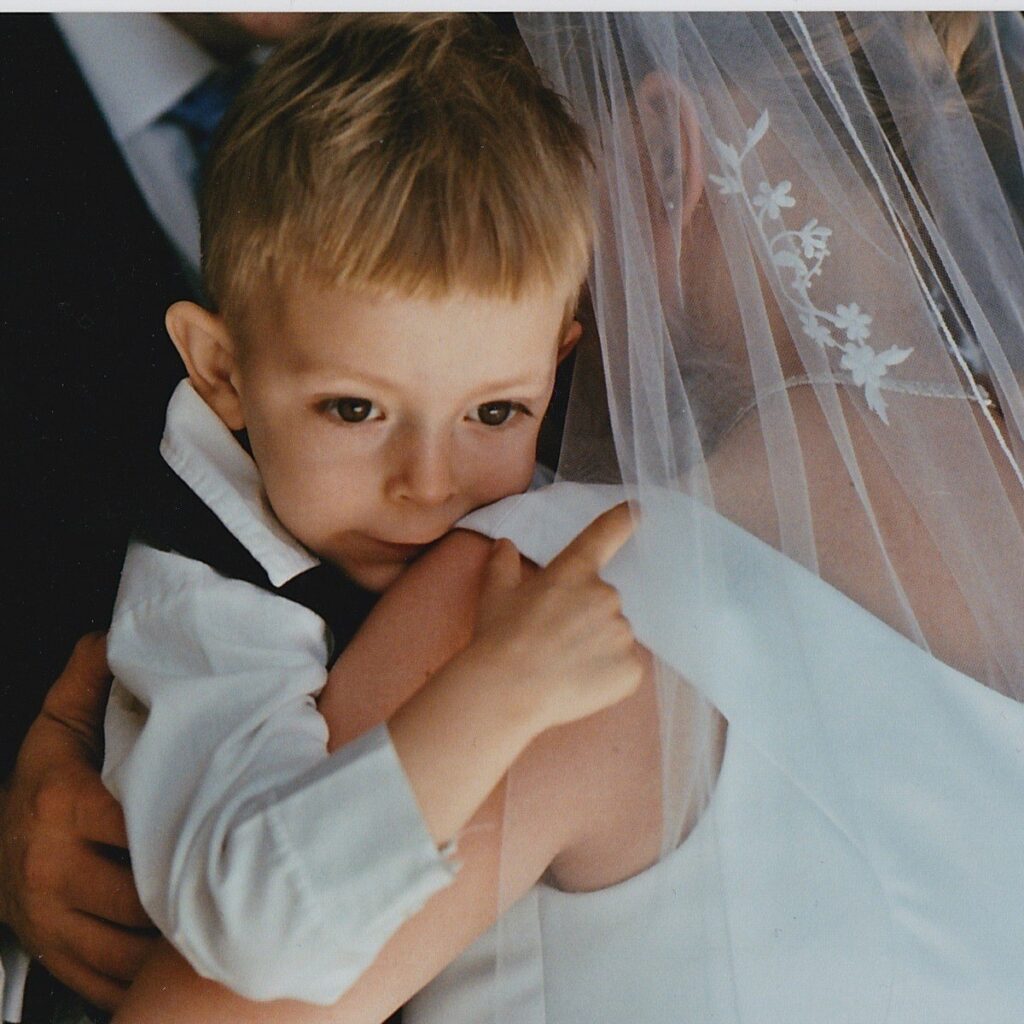

It’s a cover lesson for our neediest Year 10 English class, and on a Friday afternoon no less. They’re supposed to practise personification and metaphors, and build descriptive skills. By the very end, I manage to wrangle a dictation out of one of the boys at the back for a paragraph describing a beautiful woman.

Me: “What’s she wearing?”

Student: “Uh, she was wearing a thin layer of duvet.”

Me: “…You do know what a duvet is?”

Student: “Yeah, like a thing women put on when they get out of bed.”

Me, suspecting he means negligee or some such but not really wanting to get into it: “Okay, erm, so what are her clothes doing? Do they flow when she moves? What do they flow like?”

Student: “Like a, like a bowling ball.”

So we have a beautiful lady wearing a heavy quilt that flows like a bowling ball. At least she was clothed. Another boy kept begging me, “Can’t she just be nude?” Nope!

It’s not easy introducing characters: describing them, engaging readers with them, not oversharing. But when you’re just coming up with them, before you have to make them presentable to anyone else—that’s quite fun, don’t you think?

Starting Points

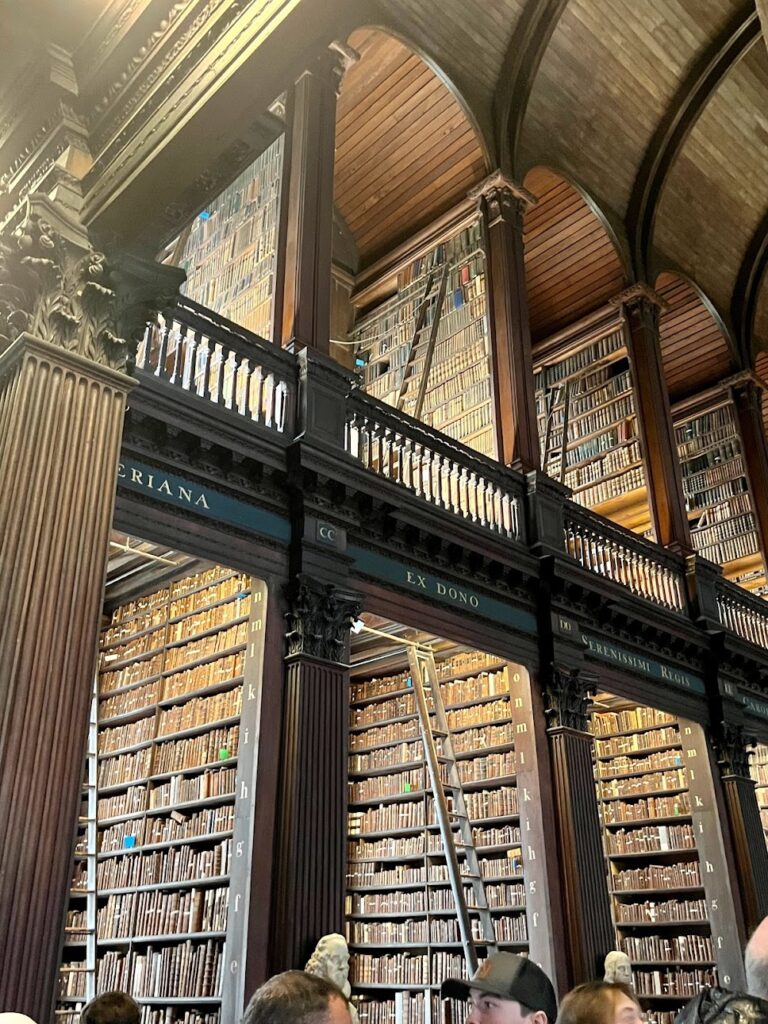

I used to start my project planning by delving into the most dramatic details of the protagonists’ backgrounds. I would use a three-pronged Harry Potter-based method: Boggarts, Dementors, and Patronuses. In other words, what was the character’s deepest fear, their worst memory, and their most happy memory.

Very important things to know. But as pivotal as those things are, they don’t control every waking moment of our lives. We’re a lot more than whatever traumatises us or even whatever gives us hope. Of course we add in interests, goals, family ties… But I think too, what reveals a lot about a character is their Default Setting.

What do they think about when they have nothing to do? Is there a daydream world they go to? Do they get caught up obsessing over past mistakes, or planning the rest of their day down to the minute? Do they play music for themselves in their minds, or play back favourite stories? That’s quite relevant to how a character presents themselves.

Rounding It Out

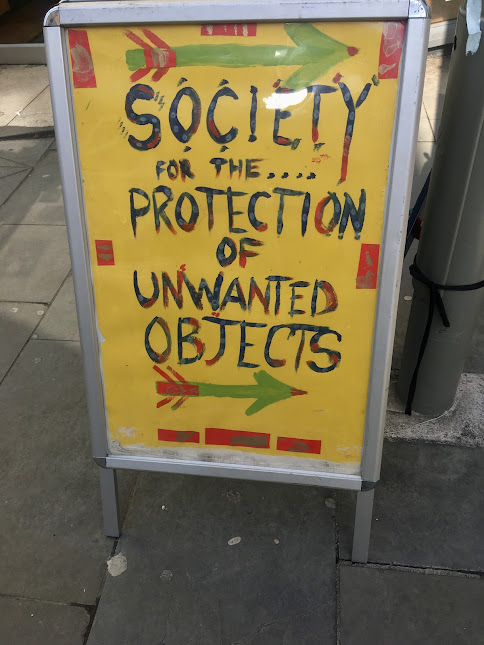

Thinking about it, a woman rolling out of bed dragging her duvet and it feeling like a bowling ball is pretty darn relatable. I might tune out if my student started droning on about a fabulous woman in an evening gown. When we’re creating characters, quirks count for a lot. A flaw can be so much more interesting than heroism.

Since I’ve been indulging in pages of possible character backstories and tastes and foibles lately, I keep thinking of two things. Firstly, there’s a wonderful speech in American Gods by Neil Gaiman, in which a young woman reels off a random list of things she believes, from firm opinions to preferences to faiths (full quote here). Secondly, and very differently, the quirky mini-bios created by Hercule, a Pet Portrait artist on Facebook. I know that sounds weird. But trust me, have a look and have a laugh.

How do your characters like their herring? Hercule often makes sure we know whether the pets he sketches prefer their herring Goth or elasticated (?!). What can your characters absolutely not stop themselves from doing when the opportunity arises? What beliefs resonate with the deepest fibres of their beings?

Planning for a potential long project like a novel, it helps if I really like my characters. Or at least, if I find them fascinating. We’re going to be spending a lot of time together; I want to make it as enjoyable and motivating as I can. Yes, my characters will go through hard times and at some point, inevitably, disappoint each other or themselves. But if I’m going to list the random things I believe in, my characters had better be included.

So, if we’re trying to make our writing fun, I suggest treating your characters like friends. Sit them down and ask questions that might not have anything to do with your plot, but could have everything to do with your relationship, and your passion for continued writing.

What would their favourite childhood books have been? The songs or artists that helped them survive their teen years, the movies or shows that recharge them in adulthood? What’s the kindest thing someone ever did for them, and the cruelest thing? What’s their favourite way to eat cheese, and how do they like their chocolate? Do they have a favourite thunderstorm memory? A favourite seaside one? Who would be their ideal animal sidekick, what would they most like to be famous for?

I hope you have a great time with your characters this week!