This Week’s Bit of String: Crosses made of sliced cheese

For Easter when I was in kindergarten, my mother cut slices of processed cheese and bologna into crosses, chicks, and egg shapes to share with my class. The school found this contribution offensive. I remember her crying over it, as she hung up laundry. We lived in a very small, seemingly homogenous New England town, but it couldn’t accommodate her humble gesture of religious expression.

As writers, we hate feeling voiceless, we hate for minorities to feel voiceless, and we should hate for religious communities to feel voiceless. I’m not endorsing the narrative of the American ‘War on Christianity.’ There’s no comparison to what a lot of BAME or LGBT people have suffered. But have you noticed a dearth of well-rounded religious characters in literature? Could this absence be feeding the fear we ‘liberals’ have of conservatives? Could it be curtailing our empathy?

Perpetuating Literary Stereotypes

I’d like to see characters like my mother in literature. Someone with unparalleled patience, raising the four children she gave birth to in five years, and working for over two decades with special needs students, often at least sixty hours a week—while dutifully living out beliefs some might view as intolerant. Someone who believes abortion is murder but who was devastated by Christian leaders’ support of a racist President who condoned sexual assault.

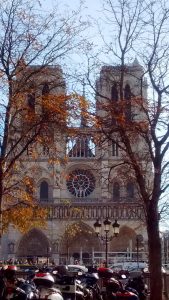

Instead, it feels as if religious characters in fiction are generally incarnations of Archdeacon Frollo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Hugo’s villain, tormented by hidden lusts, was probably a shocking revelation at the time. I’m not sure the prototype still is. In films and books, do we not at this point expect the Republicans and evangelicals to be baddies?

Admittedly, there have been appalling religious figures throughout history. One can understand the rage against clergy in, for example, Irish fiction such as The Glorious Heresies, or The Secret Scriptures. And in America especially, Christian culture, perhaps partly out of a sense it’s not welcome in the mainstream, has isolated itself to produce its own books on its own presses.

This isolation becomes cyclic. The church is the kid on the playground who has to keep his clothes clean, so he doesn’t join in football. The other kids assume he doesn’t want to play anyway—especially if he tells them they’re getting too dirty—and he resents them carrying on without him, and the gulf widens. So mainstream literature and heavily conservative, Christian literature may seem to prefer the separation. But if we consider ourselves liberal, should we ignore a whole subset of our culture?

Studies on Liberalism Versus Conservatism

Before justifying the alienation by saying Republicans are ignorant, are overly attached to their beliefs, and probably hate us too much to engage, consider these intriguing studies.

Research shows that conservative minds are more attuned to fear. Is this a cause or a symptom of conservatism? Scientific American describes how mounting scientific evidence of conservative risk awareness could explain their stereotypical attachment to rules and even nationalism.

It also explains their tendency toward idea-driven storytelling. While some conservative commentators like this one on The American Conservative website remind their fellows that using literature to mould public morals ‘leads to art becoming a mere tool, a means to an end, rather than an end in itself,’ a group will find that irrelevant when they perceive themselves under threat. Republicans (who got eighty percent of evangelical support in the presidential election) are completely in control of the American government, but fundamentalist Christians believe in Heaven and Hell. The majority of people they meet are eternally damned. If they have any compassion, they’ll try and save them with everything they do, every word they write. How could they care about trivial things like character development and artistic expression?

Here’s another surprise from a wonderful study described in The Guardian, in which literature professors researched thousands of Goodreads profiles and found over four hundred books which conservative and liberal readers frequently liked in common. Encouraging, but when they looked at the reviews, they found conservative readers were ‘more generous’ and used ‘less negative or hateful language’ than many of the liberal reviewers. We liberals can be snobby and cynical—who would have thought?

In Twitter discussion, science fiction writer Grace Crandall observes that we tend to detect biases against us: liberals see conservative bias, while conservatives see liberal bias. We’d all rather be wronged than in the wrong. But we have to rise above that as artists, and try to understand each other, as she suggests.

What is Conservatism, Really?

Everyone’s conservative about some things, and liberal about others. We all have things we don’t want to change, and things we seek to explore and improve. Micah Mattix, in the American Conservative article, reminds us genuine conservatism is ‘deeper than a political orientation; it is a temperament, one that looks to the past with reverence and the future with trepidation, and which believes that human nature is not easily changed or improved.’ Skepticism of contemporary culture is not exclusive to Republican-leaning authors.

Indeed, when we write we should examine any stereotype, even the idea that Republicans are always grouchy old white men. We write to conquer fear, perhaps our own fear of being voiceless, and it’s always worth finding characters to give voice to. There are Republicans and/ or evangelicals who strive valiantly to live up to their own standards, even if these standards manifest themselves in ways that look strange to us. In my book Artefacts, two of the protagonists are Christians, trying to establish friendships outside the church despite being convinced their acquaintances are hellbound. Religious characters don’t always have to be so dramatic; I liked the pastor and the churchgoing protagonist in Richard Russo’s Empire Falls. They were portrayed as normal people, with normal family and livelihood struggles, who happened to have a bit of faith. That’s incredibly rare in a current book, and why should it be? We’re writers. We can take on anything.