This Week’s Bit of String: Vicarious holidays to India

“You have an unusual name,” the customer on the phone says. I was typing notes on his call when he rang back and asked for me again. He explains, “We met someone with your name when we were travelling in India a while ago. Spent long, happy days watching the Ganges flow past and drinking hot chai. Was that you?”

“I’m afraid I’ve never been to India—yet.”

My colleagues nearby look up from their keyboards, distracted by my conversation.

“Well, I highly recommend it. And you understand—I had to call back and check. I thought, wouldn’t it be a shame if I missed the chance to find out?”

I absolutely understood, and thanked him for briefly transporting me from the office. Then I got sucked back into doing three full-time jobs at once, then went home to a flurry of housework, and it wasn’t until my family and I had chatted through a whole supper that I remembered this respite.

How many times have I not bothered making a connection, seizing an idea, or picking at a bit of string, because my thoughts are corralled and cornered by job worries?

On My Way to Get to the Bottom of This

There’s not much I can do about my workload while at the office, but I’m learning to take back my life after walking out the heavy, ID-operated doors.

To this end, I plan to fit reading back into my schedule, and to jot down three random observations daily. Whether it’s a funny name I heard, an interesting fact I read, a street musician I passed, or one of my son’s jokes. (Example: “I hate when people ask me where I see myself in a year’s time. I mean, I don’t have 2020 vision.”)

Don’t think me a complete slacker for not doing these things before. I finished writing a novel recently, and I’m still funnelling every spare moment into editing. I stopped reading while consumed by my own plot. That’s totally allowed.

For the last month or two, I was obsessed with my characters. In that advanced project stage, you’re trapped in a whirlpool, suffocating under the current, and the only way to relieve the pressure is through a tiny trickle—word by word. But you can only switch the outlet on when you’re not in the office, when your family doesn’t need you, when the meals are cooked and served and cleaned up, and the laundry’s done.

I did what I set out to do, sharpening my focus and finishing The Gospel of Eve’s first draft. I wrote over 80,000 words in just 2 months. But it’s probably safe to broaden my mental reach again.

Engaged in a Battle for Our Very Soul

The unexpected call-back at work came just a couple days after I spent time an early Sunday morning reading cultural articles instead of catching up on political news or launching right into edits or filling out office forms.

I read the original Esquire article on Mr. Rogers from 1998, and an NPR article about 100-year-old Arabian Nights illustrations by Danish artist Kay Nielson. Both were a treat.

It’s hard to write when you’re fretting about customers and deadlines. However, it’s also hard to distract me from my characters. And work did that, every day in the midst of penning the climax. I’d walk to work plotting battle scenes or plagues or births—and once I got to my desk, the bombardment of emails, phone calls, initiatives from supervisors and questions from junior colleagues helped me forget Eve and her descendants.

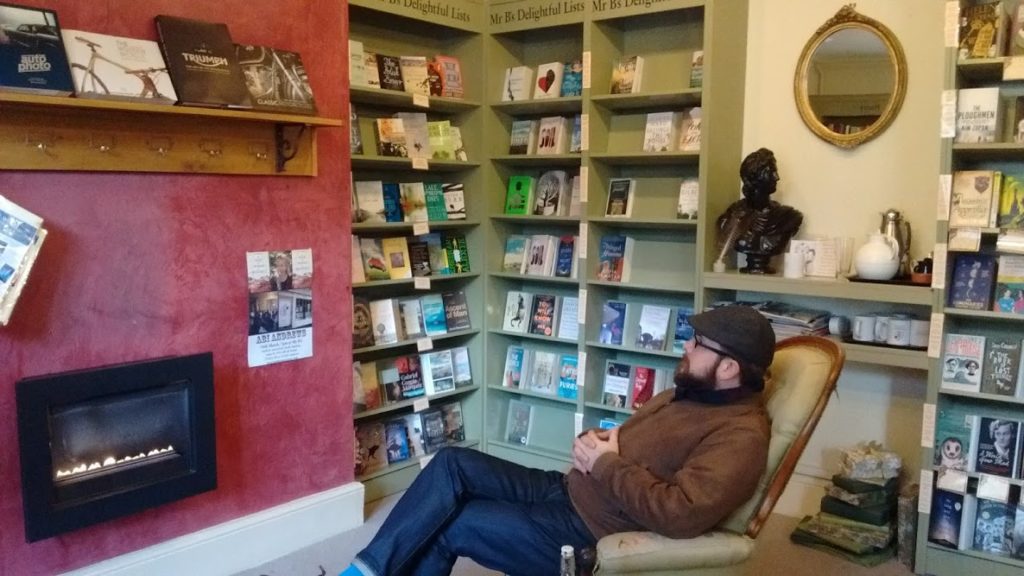

After a while I forgot it works the other way around too. If I pick up a chapter and start editing, I can disappear into Eden and its aftermath. For tougher chapters needing more work, I can ease myself in by reading someone else’s—a short story in an online magazine, or an article from BrainPickings, LitHub or Artpublika.

How do you stay creative while buried under spreadsheets? Shall we hold each other to the standard of taking in one piece of art/ literature per day, and noting down three new observations? I’ll be back at the end of the week to report. Comment here, send me a Tweet, or comment on Facebook with any suggestions and if you need any encouragement!