This Week’s Bit of String: Big wheels and street songs

We camped near Stratford-Upon-Avon over Easter weekend, our first visit there in nine years. A pretty Cotswolds town fiercely proud of being Shakespeare’s birthplace, it’s added a Big Wheel to rival the church spire and the tower of the Royal Shakespeare Company Theatre.

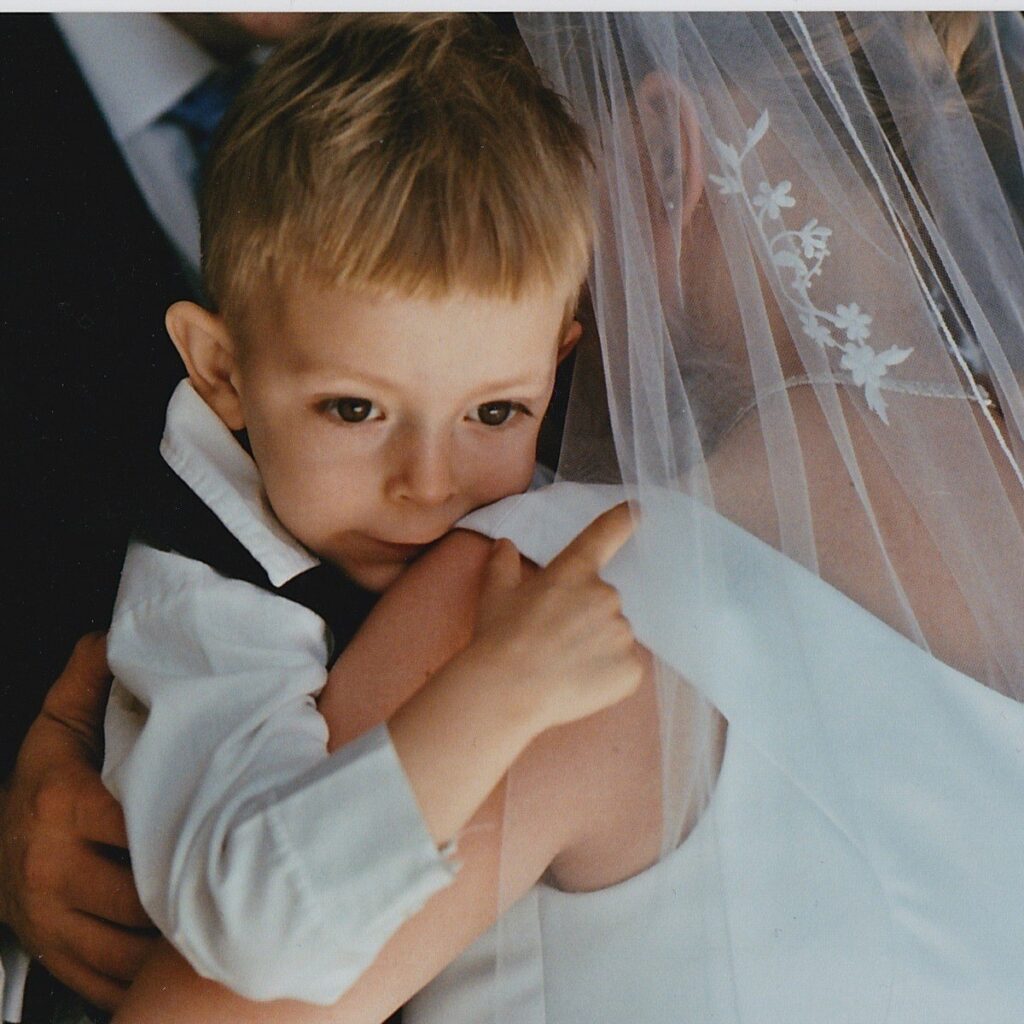

People snap selfies with the statues of famous Shakespearean characters surrounding his statue in the park. Lady Macbeth’s knuckles and the pate of Yorick’s skull are worn smooth by 150 years’ worth of tourists rubbing them for luck. Narrowboats mass on the Avon in front of them, cherry blossoms sway, and a street musician sings “To Make You Feel My Love.”

What would the Bard think of it all? I suspect he would have been okay with most developments, as long as they bring money in. And it wasn’t as if he was humourless. The range of topics he covered in his plays, he doesn’t seem completely traditionalist either.

A Theatre Trip

*Does contain spoilers for a centuries-old play about millennia-old famous historical events

My husband and I went to an RSC production of Julius Caesar while in town. It’s fascinating to me that Shakespeare chose to write this play, and frame the Conspirators with nuance and sympathy, even admiration, when he lived in a strictly royalist time. What could the preservation of democracy mean to him? This play contrasts with the anti-regicide message of Macbeth later on, for example.

We were completely engrossed by the show, although checking online later, it’s had a few sniffy reviews mixed in with decent ones. The director went for fairly plain costumes and set. There was a solemn, black-robed chorus between some scenes, just as the Greeks and Shakespeare would have intended. Between others, there were choreographed group scenes a bit like marches or parties or riots.

This aspect was quite different and a little confusing. I’d looked at the cast list already, though, so I could pick out Brutus and see that her motions represented her inner conflict. I do wonder if some of the same people who criticise the choreographed segments as being too gimmicky, too distracting or confusing—might those not be the same people who advocate for opaque literature, for leaving things up to interpretation? So, I have interpreted it, and find it interesting, and thoroughly believe I would pick up more detail if I had the time and means to see it again.

Both Brutus and Cassius were played by women, which I felt made their friendship more moving, particularly in their parting scene. They were sisters-in-arms. Maybe I’m being egocentric and enjoying a chance to see my gender reflected more in traditional theatre. But perhaps there’s also an objective poignancy in seeing two women take on the accepted power structure, rather than two men do it.

At least one reviewer, as well as an elderly theatregoer my husband overheard, complained about how these two leads kept male character names while using female pronouns, and also kept some lines referring to the characters as men. I was not flummoxed by this. When Mark Antony repeats in his famous speech, “But Brutus is an honourable man,” it’s obvious who he’s referring to.

I wonder again if people who quibble over the lack of matching names/ pronouns/ gender language will wax lyrical about symbolism and analogy in Shakespeare. I suspect they know he’s not always literal. Maybe they just have certain buttons that get pushed when a young Black woman plays Brutus.

Death Scenes

The actress playing Brutus is Thalissa Teixeira, and she was riveting, with a cool elegance befitting an honourable soldier, and moments of passion which showed why she would have such loyal friends. She has ties to Brazil, and you can read how that influenced her portrayal of political upheaval and rebellion.

Brutus’s servant Lucius was played by Jamal Ajala, a deaf actor of colour. So some scenes at Brutus’s house were signed as well as spoken, and the director Atri Banerjee chose to have Lucius reappear in the final scenes as the friend who assists Brutus’s suicide. Brutus’s request to him and his acquiescence were completely silent, only signed. This made it much more striking.

I had to read a lot of Shakespeare in my American high school and university years, much more than the strictly exam-based curriculum in Britain demands. Having been inundated mainly with his tragedies… they get a bit samey. There’s a lot of hand-wringing leading-up-to-death scenes, and this version put the hands to good use. For a taste of what I mean, here’s a video of Jamal Ajala performing Hamlet’s soliloquy in British Sign Language.

Shakespeare bestows an element of control on his characters’ deaths. People get to have little speeches and even Caesar, after he’s been stabbed by several people, doesn’t die until he’s sort of consented to do so: “Let fall Caesar!” This must have been how Shakespeare wrestled with the brutality of life in Tudor/ Jacobean times, when there probably weren’t many poetic farewells. Not during executions and plagues. I doubt he would have begrudged today’s directors and actors using his work to make a mark on society, to make it more inclusive and diverse.

What do you think about Shakespeare, and about reinterpretations of it? Is adding a Big Wheel to the literary landscape a betrayal tantamount to what Brutus did to Caesar?