This Week’s Bit of String: An air of incredulity

“Miss, how are there people who like to read?”

I’d been scribing answers to questions about Lord of the Flies while the severely dyslexic GCSE student dictated. He was then curious about why there are “neeks” (the word “geek” has evolved) like me who actually enjoy books.

“Well,” I told him, “I got to like reading because I was taught so many different books at school, I knew there were loads of great options.”

The openness of the question surprised me and I should perhaps have been more emotive, told him how reading takes me out of my own life and into different worlds. Or that it’s easily as entertaining as TV. I wish I’d had more time to tell him that with books, there really is something for everyone. As long as they can access it–which unfortunately, he physically cannot.

I wonder if this young man gets the sense of luxuriousness from playing videogames which we find with books. Books free us from having to compete. They offer immersive surrender, and that’s what I crave sometimes. It’s liberation from being in life’s driver’s seat.

Again, this only works if you can access it. We all go through stages when there simply isn’t time to read much. Sometimes I find myself reading with a grim desperation to tick books off my reading list.

I remind myself that this is love. As with any relationship, we sometimes get caught up in our duties of care; keeping everyone fed and happy. But the love is there. When it comes to reading, I ensure I take the time to write down my favourite quotes, to reflect in my daily scribbles, before starting something else. It’s not a chore.

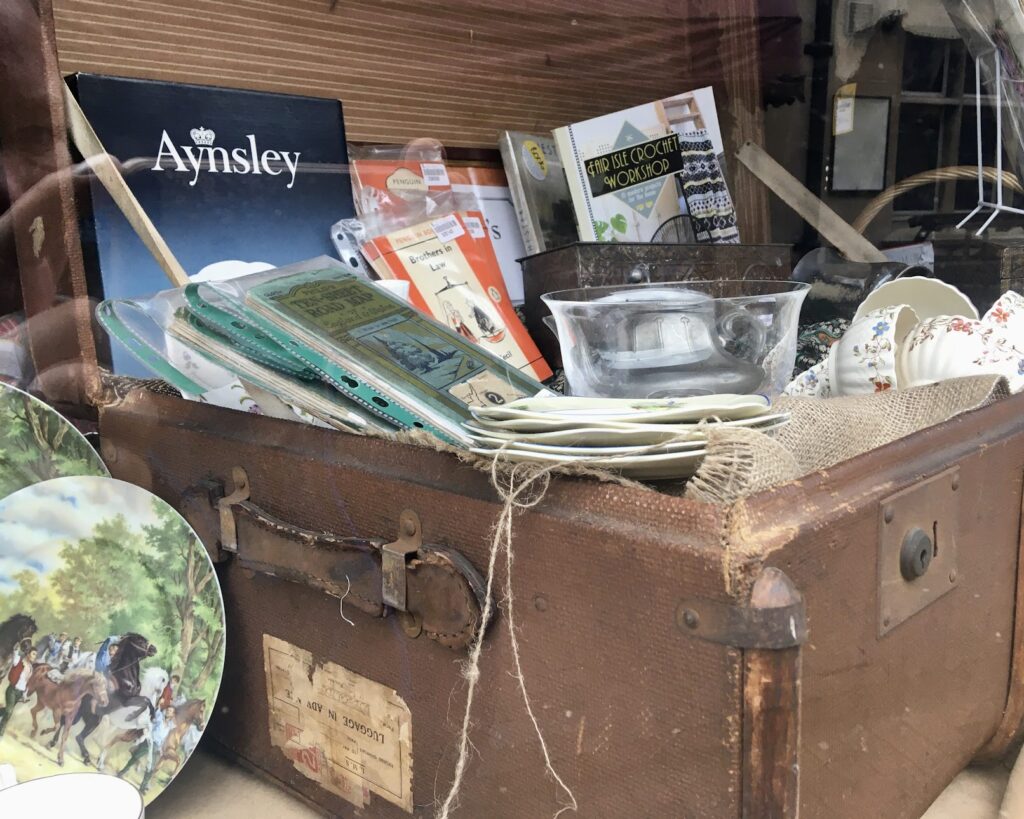

Burrowing and Borrowing

I spent last weekend at Hay-on-Wye Literature Festival. If you ever need to rekindle your love for reading, it’s a great place to do so. Sunny but chilled, colourful yet somewhat calming. I guess that’s because even though I’m among crowds, they feel like my people.

Not that Hay’s festival-goers are in any way homogenous. As with writers, there are all sorts of readers. Young and old, Welsh or English or from further abroad, people in motorised wheelchairs or with support dogs. At an evening talk I also noticed another woman on her own, like me, pencilling tiny notes.

In both the first talks I went to, though they were on very different topics, the writers talked about being magpie-like in storing and selecting detail. Marina Hyde, the Guardian columnist on current events, peppers her pieces with pop culture references. Peter Frankopan, a passionate historian who’s recently written about natural disasters throughout history, drew on so many different sources he ended up with 4000 footnotes in his latest book.

Later I enjoyed wonderful readings from the poet laureate Simon Armitage. He opened with “Thank You for Waiting” (have a listen here!) and he talked about how hard it was during lockdown to be inspired without everyday interactions and excursions. He calls those the “cement” which sticks our writing together. Trying to create in his upstairs office, he found himself writing poems about Velux windows.

The reason there are enough books in the world to interest any reader is because writers are so diverse. And maybe when we love our art enough, we can find ways to write about anything.

Safety in the Pages

Beyond offering inclusion, books throughout history have bestowed security. We listened to Irene Vallejo talk about her volume Papyrus, which uncovers the history of the written word. She shared stories of the library of Alexandria, and told us how things changed with the development of the Latin codex.

The codex, with similar etymological roots to the word book, means block of wood, or tree trunk. Instead of being a long, flattened scroll you’d have to roll back up for storage, the codex used sheets bound together like modern books.

This change wasn’t just culturally significant. It also made reading a safer hobby. In times of religious persecution, for example, Christians could read in codex form. Should someone come along, they could close the codex and stow it away as a humble block, thus keeping secret the substance of their reading.

I loved learning this bit of history. Even now, in our privileged times, there’s something reassuring about wandering around an event where lots of people have books under their arms or noses. Just a bunch of bookworms sharing a common love if not common tastes, and although there are plenty of magpies about, they’re the curious rather than vicious kind.

What makes you fall in love with reading?